By Kevin Rabalais

Sometimes you have an obligation to say it while it’s hot. You encounter a new writer and feel the charge of her work in ways that make you want to drop the façade of the third-person. And so let it begin, here, with a shout from the rooftops:

I have a new hero, and her name is Samar Yazbek.

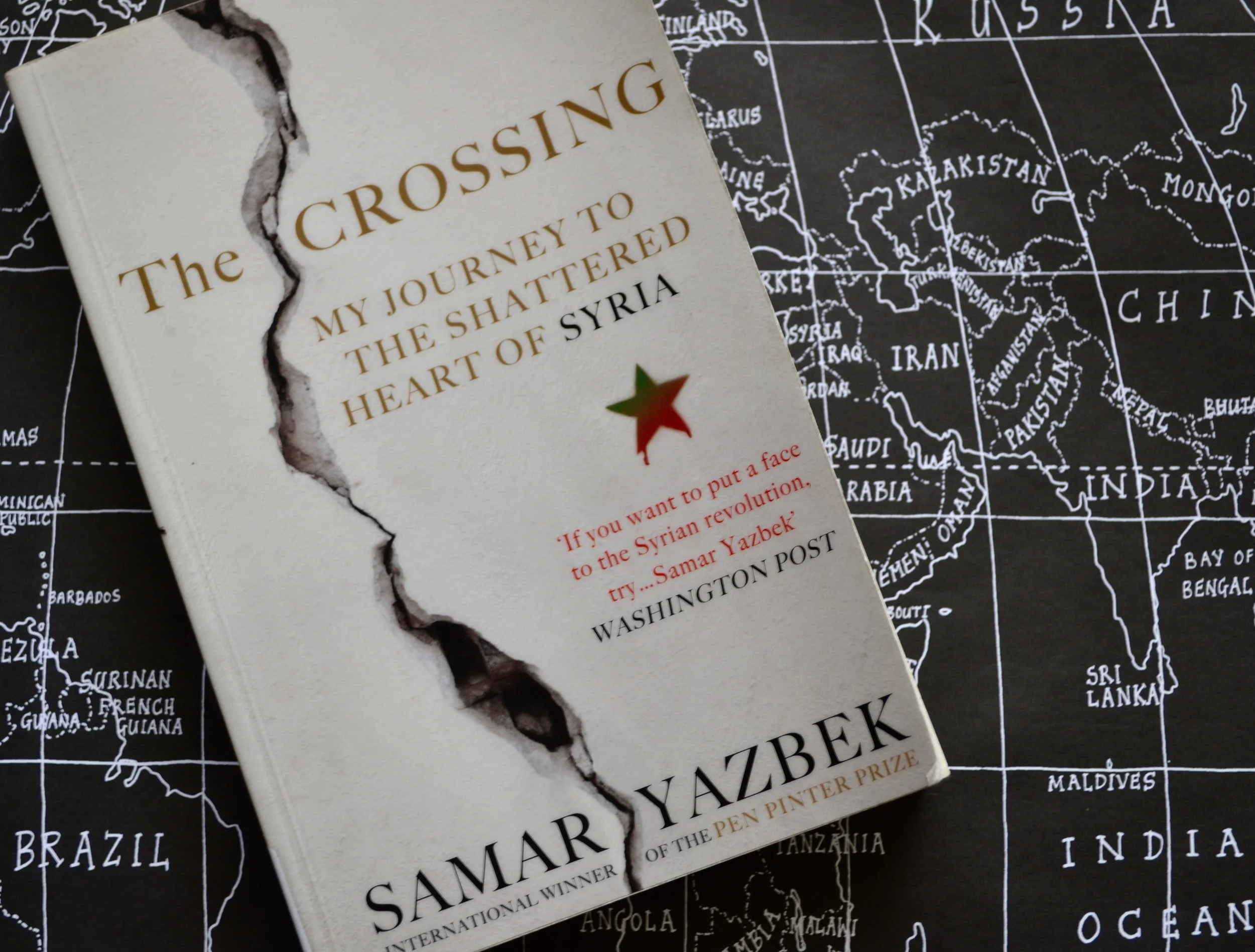

A little background. For her participation in demonstrations during the early months of the Syrian Revolution, Yazbek had to flee her country. More specifically, in July 2011, the Assad regime forced her into exile. Among her crimes: she had published articles, as she writes, “outlining the truth about the actions of the intelligence services, who were murdering and torturing those protesting against Assad’s regime.” In The Crossing: My Journey to the Shattered Heart of Syria (2015), Yazbek describes being pursued by Syrian intelligence services and escaping with her daughter to France.

“If we die now, the world will know our story, won’t they?

”

Once settled in Paris, she feels the exile’s discomfort. Yazbek writes of sitting in a café in the Place de la Bastille “sipping my coffee under a gentle sun, with lovers on my left exchanging kisses, when a sparrow landed on my knee making me leap to my feet in panic—that wasn’t home, that was exile.” Rather than find the setting tranquil, it reminds her that the deepest pain of her separation from Syria has been the involuntary disengagement from her beliefs. In The Crossing and essays such as “Divisions or Unity? Art and the Reality Behind the Stereotype”—which is collected in Life from Elsewhere: Journeys through World Literature—Yazbek proves herself the kind of engaged writer we find in Malraux or Orwell. You read this work and want to write a memo to the Swedish Academy.

In August 2012, thirteen months after her forced exile, Yazbek traveled to Turkey with plans to make the dangerous crossing over the Syrian border.

…having arrived in France, I’d felt compelled to return to northern Syria, to fulfill my dream of achieving democracy and freedom in my homeland. This return to the country of my birth was all I ever thought about, and I believed in doing what was right as an educated person and a writer, standing alongside my people in their cause.

Between August 2012 and August 2013, she made not one but three separate crossings.

Everything I recount in the following narrative is real. The only fictional character is the narrator, me: an implausible figure capable of crossing the border amid all this destruction, as though my life were nothing but the far-fetched plot of a novel. As I absorbed what was happening around me, I ceased to be myself. I was a made-up character considering my choices, just able to keep on going.

Yazbek began these journeys with the goal of establishing “small-scale” projects for women and to provide children with education. “If the situation was likely to be prolonged,” she writes, “there was no choice but to try to focus on the next generation.” In June 2012, shortly before her first reentry into Syria, she established Women Now for Development, an NGO whose aim is to empower Syrian women.

In the process of sneaking across the closed border and with the number of jihadist fighters wishing to enter Syria on the rise, Yazbek discovers the complex and dangerous world of moneymaking in people smuggling, a field as male-dominated as her native country. She employs her skills as a novelist (she has published several works of fiction, including Cinnamon, as well as A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution, for which she received the Pinter International Writer of Courage Award) when examining the violence and, most importantly, the countrymen and countrywomen she encounters and who live with that violence every hour.

Of course, whenever I traveled back to Syria, most men couldn’t resist mentioning the fact that I’m a woman, and that this was no place for a woman. The fighters I was surrounded by this time were tall and thickset, with strong, clear eyes and long beards. They would never turn their heads to look at or say a word to a girl. Yet what many might interpret as signs of manhood and bravery seemed to me like an indifference about life and death. They were searching for the gateway that would lead to the eternal paradise that had been promised them. Rather than be inspired by them, I could only pity them.

Once inside Syria, Yazbek travels with her guides and sleeps in the homes of their families. She opens these interiors for us, granting us access to the stories of those who endure more hardships in a day than most privileged undergo in a lifetime. We listen to mothers wait for the silence between sniper fire so that they can tell their children when it’s time to play again. “This is the catastrophe that Syrians deal with every day,” Yazbek writes, in this country made of “clay, blood and fire, and ceaseless surprises.”

While Yazbek proves to be a philosophical guide—think Didion meets Kapuściński in the furnace of the Middle East—she is also a great listener. She allows the Syrians she encounters to talk. And once they start, she learns, they want nothing more than to be able to continue. One of these women speaks of her suffering until her voice grows hoarse.

She didn’t stop talking, ignoring the noise of the shelling, and I didn’t stop writing. …

“That’s enough,” she said, grabbing my hand. “If we die now, the world will know our story, won’t they?”

“Yes, they will,” I answered, without hesitating or trying to console her.

You can see the images in newspapers. You can watch the footage on television, but this kind of reportage—rarified and harrowing—allows us to move among a population trapped in the vise of three factions: ISIS, Assad and the Free Army, or as one of the Syrians Yazbek interviews calls them, in the same order: “those dogs, the regime [and] thugs and looters.”

Yazbek gives us the names and faces of those living through this great rupture in history: she invites us inside the sorrows of their days and demands that we feel.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us via Facebook or Twitter.