By Kevin Rabalais

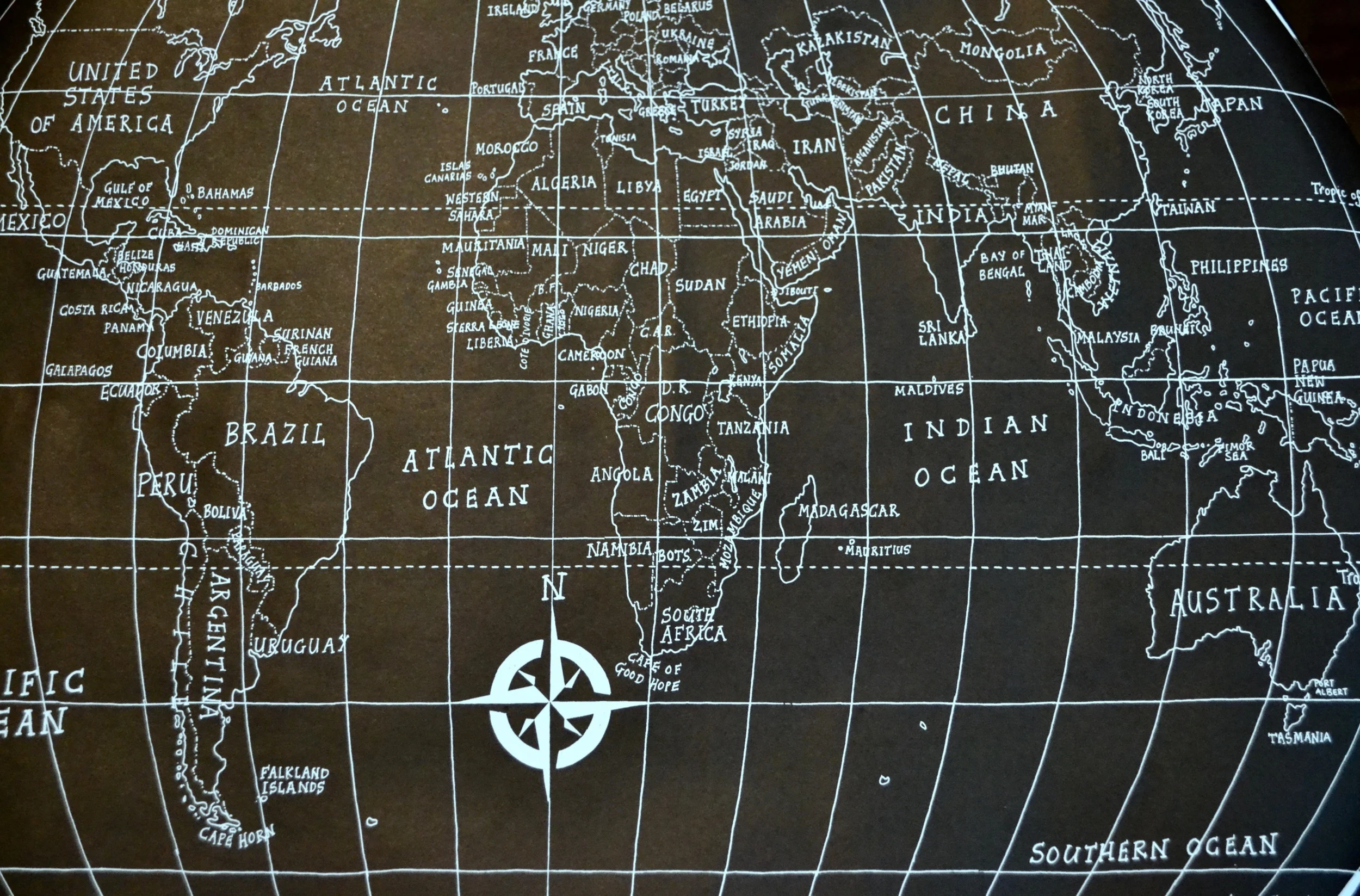

Some books are like libraries. They provide direction to a multitude of other books, other ideas. We move through their chapters much as we navigate through rooms in a house. Even after a lifetime of rereading—or revisiting—the best of them continue to reveal unexpected corridors and hidden vaults. There, we find names of writers whose works are like continents awaiting our exploration.

Literature reminds us that we should never be afraid to look at something as though we’re witnessing it for the first time, however well we think we know it. This is one reason great books offer endless company and sanctuary. Each expedition into them reveals new vistas: the book becomes more intelligent as we grow alongside it.

Occasionally, our good fortune allows us to discover the kind of generous volume that grants wisdom in its own pages and a card catalogue’s worth of recommended readings. Engaging with such a book is like having a conversation with one friend who can’t wait to introduce you to another, someone you’re certain to admire.

Any fan of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, for instance, has likely found such a companion in the author’s The Art of the Novel. On first impression, Kundera’s book of essays provides an education in the evolution of a genre. Steep in it for a while and discover—or let Kundera help you remember—some of literature’s great constellations. Consider the list from the first pages alone: Cervantes and Diderot, Novalis and Flaubert, Musil and Broch, Joyce and Mann, Kafka and Hašek.

The Art of the Novel helps us find a use for those extra blank pages publishers often include at the end of books. That white space elicits our side of the conversation; it permits us to create our own lists or indexes and to engage in a dialogue with the book. This dialogue also becomes a conversation with ourselves as we revisit the book over a lifetime.

Make a list of the names Kundera mentions in The Art of the Novel and you will have enough directed reading to provide sustenance for decades. So, too, with the list the wise team at Pushkin Press and English PEN has assembled in Life from Elsewhere: Journeys through World Literature.

In 2005, Bloomberg and Arts Council England established English PEN’s Writers in Translation, a program that has funded the translation into English of hundreds of books from nearly fifty languages. The November 2015 publication of Life from Elsewhere marks the program’s tenth anniversary. It’s an indispensible anthology of essays for anyone who reads to live and knows that rather than an escape from reality, reading permits a plunge into the world. This collection is for those among us who feel literature.

Life from Elsewhere includes contributions from Turkey (Elif Shafak), Israel (Ayelet Gundar-Goshen), Iran (Mahmoud Dowlatabadi), China (Chan Koonchung), Syria (Samar Yazbek), Poland (Hanna Krall), Gaza (Asmaa al-Ghul), Russia (Andrey Kurkov), Spain—by way of Argentina (Andrés Neuman)—and the Congo (Alain Mabanckou). Its intention, as Amit Chaudhuri (India) writes in his introduction, is to locate those places and voices too often overlooked:

“Our challenge is to recognize the invisible for what it is, and, through it, to try and access the different, interrelated, competing points of excitement that have made up our world.”

Literature continually reminds us that we are not alone and (to paraphrase Kundera) that things are not always as simple as they seem. With so many stories, histories, characters and figures populating a reader's mind, it's easy for us to take for granted the liberation that literature imparts. Considering our wide and fast access to books, this may be truer now than ever before.

Not so for those in Gaza, as Asmaa al-Ghul writes in Life from Elsewhere:

This is what the blockade does to the Gaza Strip: it imprisons the mind. The blockade is not about making people starve; it’s about whether they can travel and immerse themselves in new experiences, enabling them to breathe new life into their thoughts and understand that, as humans, we are changeable beings; we shift and might believe today what we opposed yesterday.

Each of these essays reminds us that to fully inhabit our own skin, we must learn to shed it and enter the lives of others. These ten writers invite us to take long looks at things. They invite us to ask questions. They remind us that those questions are often best when we begin at square one. “Isn’t engaging with others more important than being divided by race, ethnicity and religion?” al-Ghul asks. (As for her other advice: “we need to learn to apologize when we are wrong, and to thank others when they have taught us something.”)

Dowlatabadi—author of Thirst, a harrowing novel of the Iran-Iraq War—warns of the dangers of closing a different kind of border.

“Over the past thirty-odd years,” he writes, “I have personally not heard any news about any literary work of some weight or worth being displayed in the windows of bookstores in [Tehran], in my country. And if there are some, there’s hardly ever a reader to purchase it.”

He and others warn of dangers that fall between the visions of Orwell and Huxley. In the latter’s vision, as Neil Postman writes in Amusing Ourselves to Death, “no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history. As [Huxley] saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think. What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who would want to read one.”

Shafak addresses the problems that emanate from what, in some of these writer’s countries, infiltrates society as a combination of both of the above. “It is ironic that in a world where more and more people dream in more than one language, we are constantly being asked to reduce ourselves to singularity,” she writes. “But the human being, by nature, is a conglomeration of multiple voices. Each and every one of us retains myriad selves. We are never just one single identity.”

And through literature we have access—no border control, here—to the thousands of places and people our own limited lives will never otherwise permit us to see and know. Yazbek addresses this in her analysis of what it means to read a great work such as Les Misérables:

A character like Gavroche Thénardier, a young boy who died in the 1832 uprising, makes more of an impression on us than any number of political slogans; he is a vivid historical personality who will never die. A character like this makes us feel we share in his history, in his personal tragedy, and this is the magic of literature: that deep human sense of belonging, of empathy, that displaces our own national and religious loyalty and encourages us to identify instead with the idea of free humanity.

Sometimes it’s best to remember that the simple question—the kind al-Ghul poses—is anything but simplistic. Sometimes it’s best to stop and say thank you. As in, thank you, Writers in Translation, and thank you, Pushkin Press, for providing, in one volume, introductions to ten writers—a portable library of world literature. Each of these authors has a book or multiple volumes available in English. They remind us that it’s less a matter of Literature or Life, as the Jorge Semprún title has it, than Literature for Life. Or, as Yazbek writes, that “Literature is our parallel life, the place where history becomes immortal.”

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us via Facebook or Twitter.