The first sentence of a novel should be something you can fold up and carry around as you move through the rooms of the book. At any point during the reading, you should be able to hear it, recall it in full, unfurl it and explore its essence.

Whatever you believe about reading, you know the ways that great sentences stay with us. They’re the ones that we find ourselves repeating as we walk down the street on a Wednesday afternoon long after the book has gathered dust on the shelf. The ones we underline or copy into a notebook for some future purpose we can’t name. The ones that send a charge up our spines.

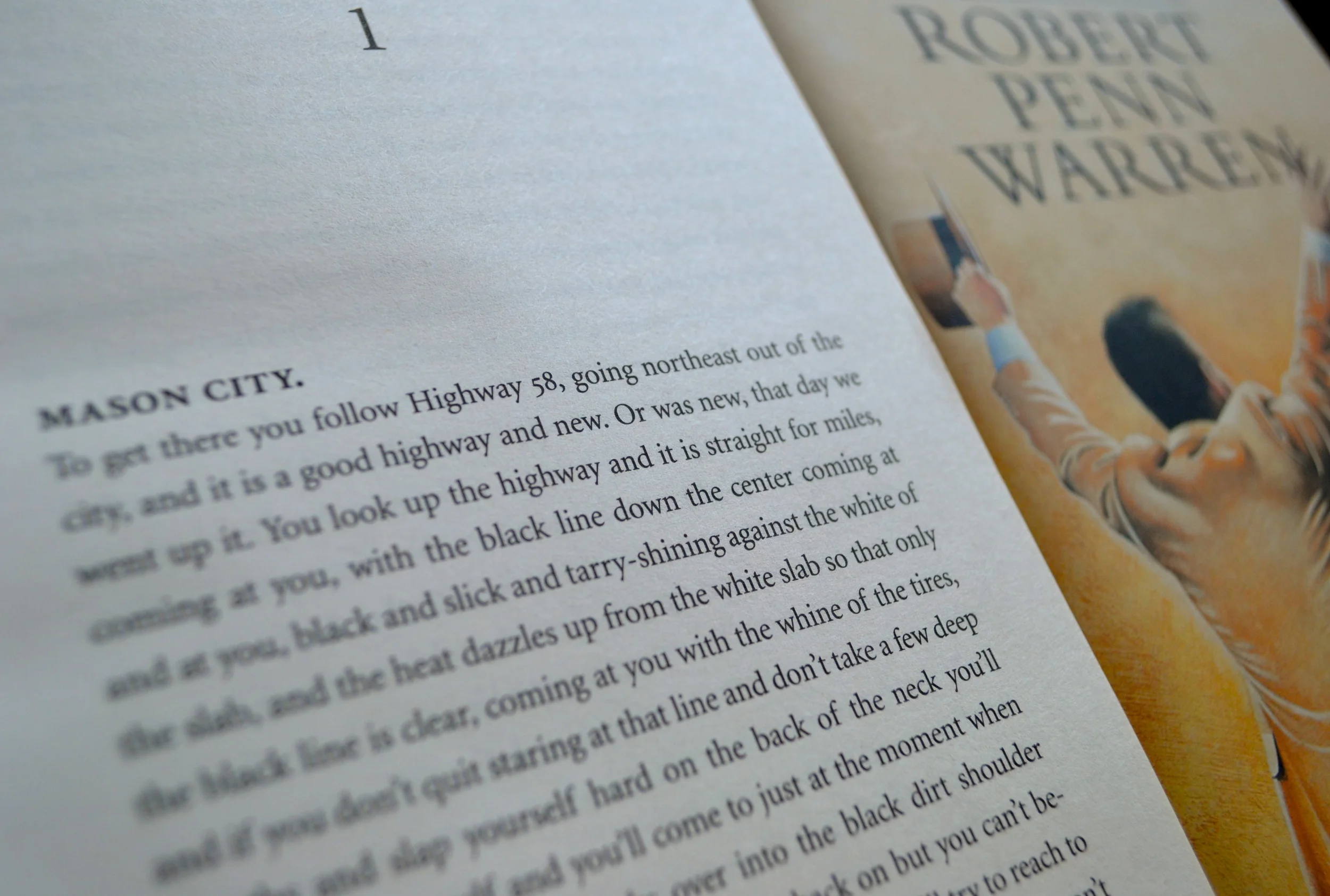

Thinking about the power of sentences in fiction got us musing about one of our favorites. It’s not the opening or closing line of a novel, but the 151-word third sentence (or fourth, if you count the opening words of the book: “Mason City.”) in the first paragraph of Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 novel All the King’s Men, which won the Pulitzer Prize (his first of three) the following year.

Here it is in full. Take a deep breath and try to read it aloud in one sputtering rush:

You look up the highway and it is straight for miles, coming at you, with the black line down the center coming at and at you, black and slick and tarry-shining against the white of the slab, and the heat dazzles up from the white slab so that only the black line is clear, coming at you with the whine of the tires, and if you don’t quit staring at that line and don’t take a few deep breaths and slap yourself hard on the back of the neck you’ll hypnotize yourself and you’ll come to just at the moment when the right front wheel hooks over into the black dirt shoulder off the slab, and you’ll try to jerk her back on but you can’t because the slab is high like a curb, and maybe you’ll try to reach to turn off the ignition just as she starts the dive.

And then the next, which arrives like a blow: “But you won’t make it, of course.”

Listen to those rhythms. Warren’s sentence chugs along, repeating key phrases to punctuate and propel the tempo, urging you to move faster and become wilder. We don’t know yet what’s happening, but we know that this unnamed peril is manmade and avoidable but too alluring to deflect. The sentence becomes the movement of the car (and its driver’s impulses), taking on the shape of the action. It builds and builds, pulsating with beautiful repetition until the reader falls breathless and out of control. But this isn’t a crash; it’s a controlled un-control, and you’re happy to careen along.

What a wonderful metaphor of everything that is to come in this stunning novel of a self-made politician drunk on power (and the people he lulls into the exhaust of his fumes) that speaks today even louder than it did nearly seventy years ago. After the wild journey, what a tremendous plummet Warren invites us to expect. What a deafening boom after such a melodic scat: “But you won’t make it, of course.”

JL & KR

You can find Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men at Avenue Bookstore and all good bookstores around Australia, through Amazon and at your neighborhood bookstores in America.

To subscribe to Sacred Trespasses, send us a message with the subject “Subscribe” via our contact page, or follow us on our Facebook page.