“Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities. Truth isn’t.” Mark Twain, Following the Equator

Put it in a novel and no one would believe it. Son of one of Italy’s wealthiest families, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli joined the Communist party shortly after his twentieth birthday. The next year, upon his inheritance, Feltrinelli became a significant supporter of the party. He also began to finance an extensive library of radical literature. As Peter Finn and Petra Couvée write in The Zhivago Affair, Feltrinelli’s wealth allowed him to purchase rare books across Europe, thousands of volumes that included a first edition of The Communist Manifesto, as well as notes of Marx and Engels, a first edition of Rousseau’s Social Contract and Hugo’s letters to Garibaldi.

A love of books eventually led Feltrinelli to publishing, and soon he owned his own company, Feltrinelli Editore, based in Milan.

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, Boris Pasternak had started to show Dr. Zhivago to foreign readers. One of them, Sergio D’Angelo, smuggled a copy from Pasternak’s dacha to Berlin. He called Feltrinelli in Milan. The publisher flew to Berlin to collect the manuscript.

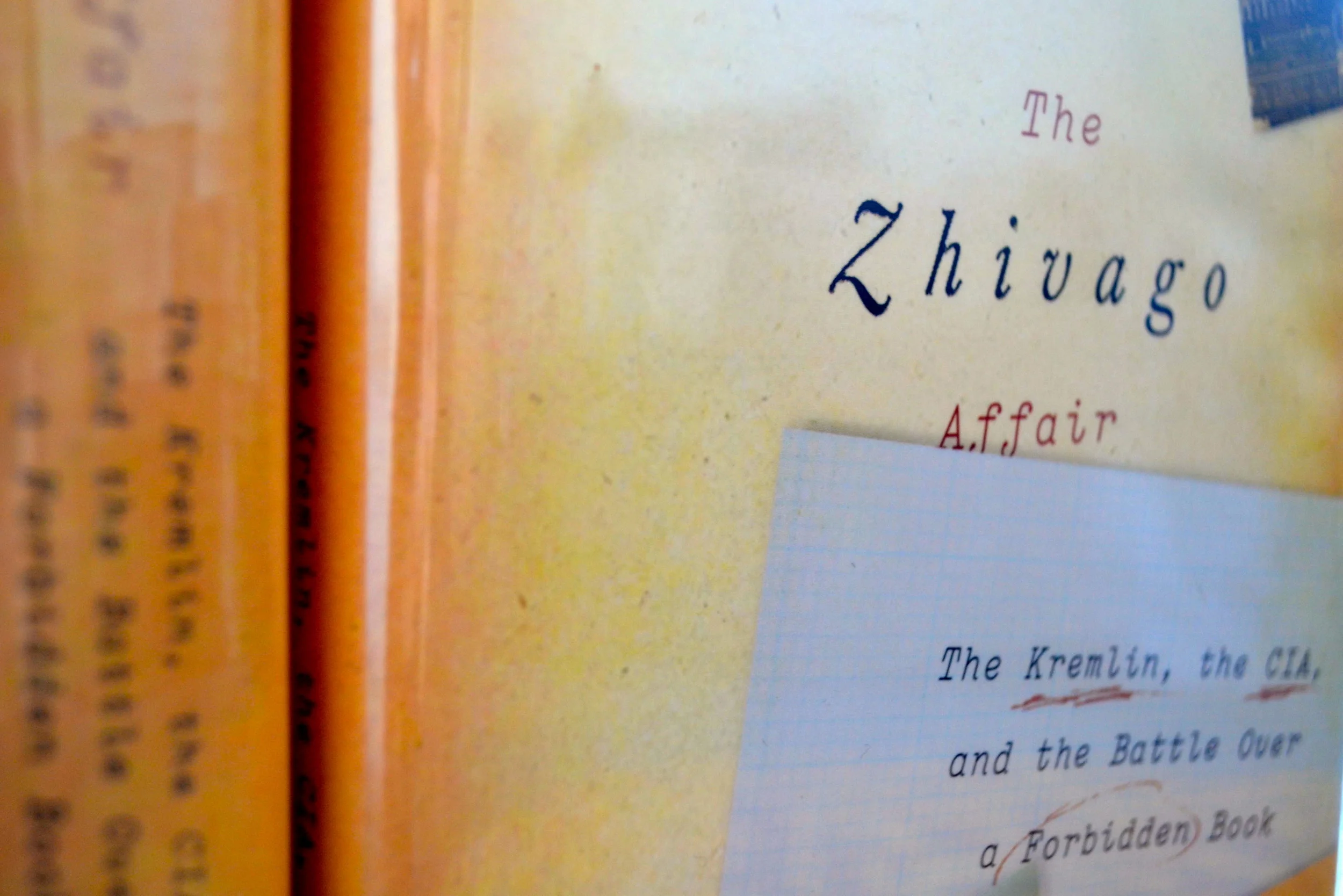

The story of Dr. Zhivago’s publication in the West reads like a spy novel, a true-version of the labyrinthine thriller that unfolds in Charles McCarry’s The Secret Lovers, which follows a CIA plot to publish a novel by a Soviet dissident and, in the process, try to bring down the Soviet Union. That’s one reason why Finn and Couvée’s The Zhivago Affair reads more like a novel than a work of history. It’s the kind of book that at once reminds us of the power of literature and makes us long for the days when the CIA believed that books could be more powerful than weapons. But this is about Feltrinelli.

After he brought Dr. Zhivago to life in the West in 1957, Feltrinelli spent the next decades traveling the globe. He met Third World leaders and published the work of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and Ho Chi Minh. Then on March 15, 1972, the man whose family name had become synonymous with the industry of northern Italy—a name that ranked among Agnelli, Motta and Pirelli, as Finn and Couvée write—was found dead under a high-voltage electricity pylon in a Milan suburb. A member of the left-wing militant organization GAP, Feltrinelli, code-named Osvaldo, had climbed the pylon with plans to cause a power outage across Milan. His bomb went off early.

Pasternak received the Nobel Prize in 1958, one year after Feltrinelli published Dr. Zhivago. Two decades later during an anti-terrorism trial, members of the Red Brigades discussed their relationship with “Osvaldo.” They noted the technical problems that led to Feltrinelli’s death and the failure of his mission. More than twenty years after that trial, the Corriere della Sera reported a different story: Feltrinelli had been mugged and tied to the pylon before the bomb exploded.

“It’s no wonder that truth is stranger than fiction,” wrote Mark Twain. “Fiction has to make sense.”

KR

To subscribe to Sacred Trespasses, please send us a message with the subject "Subscribe" via our contact page.