We first met Michael Martin in the legendary—mythical, in our view—Maple Street Book Shop in New Orleans in the late 1990s. A single name, Andre Dubus, revealed shared literary sensibilities, and we became fast friends. Over the years, we were happy to serve as advisory editors of Hogtown Creek Review, the literary journal that Michael founded and co-edited and which was based in Gainesville, Florida, and Amsterdam—two of his many homes over the years.

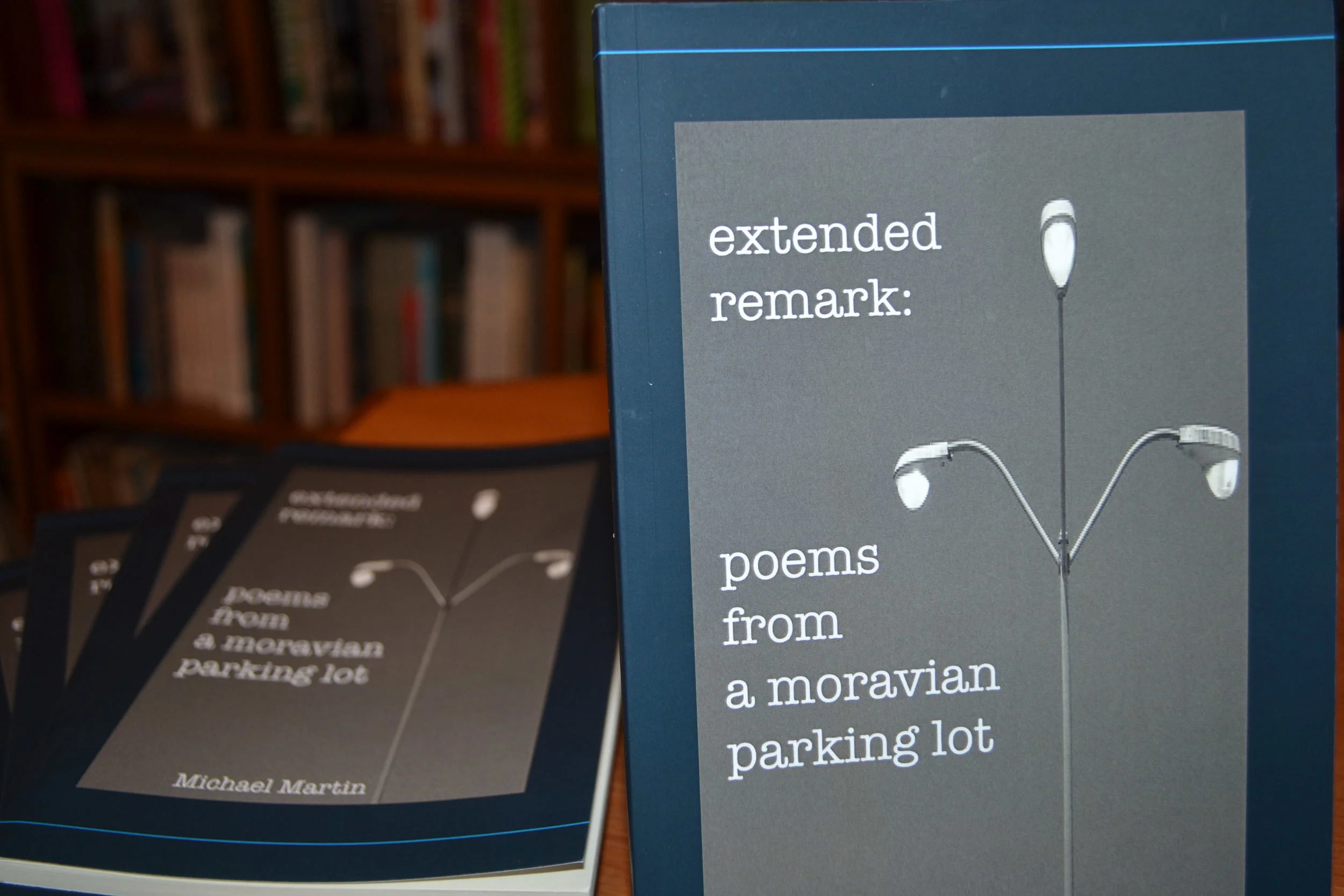

Michael’s poetry has appeared in numerous journals and magazines including the Chattahoochee Review, Carolina Quarterly, Mangrove Magazine, Berkeley Poetry Review, Gargoyle and New Orleans Review. He is co-editor of Rules of the Game: The Best Sports Writing from Harper’s Magazine (2010, Franklin Square Press) and author of extended remark: poems from a moravian parking lot (Portals Press, 2015).

This month, in between readings and events, Michael sat down to answer a few questions about his writing and reading for Sacred Trespasses.

Russell Shorto’s blurb on the back of your new collection, extended remark: poems from a moravian parking lot, says, “If you challenged Michael Martin to a duel, his choice of weapon would be the idiom.” Your work has a fluid style that is deceptively casual. How did you locate that voice, that form of expression?

More than any other—let’s call it “rhetorical device”—the thing that sets the table for me is voice. I think any writer worth his or her salt has this in spades. It’s what I’m hoping to hear when I pick up some lit or watch a movie or listen to music. Barry Hannah once said he couldn’t care less about plot in his stories and that all he needed was a voice, and if he had that, he could get away with murder. (He did.) I find if I have a first line (I call this the Title), I’m off to the races, though said first line, I assure you, will be effaced after a few turns, if the poem is working.

When I write I always hear the casual and colloquial in my little noggin; I hope if any reader hears a voice in the poems they hear that too; I wish it to be an invitation of sorts. An idiomatic sing-song American vocab is what echoes down my halls. I throw in with that. It’s at, the very least, the only way for me to approach the big, bad-ass blank page. The unadorned and natural is a powerful, beautiful thing in American literature. Someone called it The Grand and the Plain. Comes from the ear, I think; a bodacious amount of listening. To everything. Since I’d rather make a poem than make interesting writing, a natural voice seems to serve my stuff pretty well. It certainly wasn’t designed that way (what was?), but that’s what’s surfaced after a bazillion hours of writing and reading and listening.

What role does this listening play?

When I was just a young thing in my early twenties, I lived across the street from Harry Crews. I worked the night shift at a beer factory outside of Gainesville and so came home about dawn every day. So did Harry. Sitting on my front porch drinking an end-of-shift tall-boy, I would often see a cabbie drive up to Harry’s house, pull drunk and drugged Harry out of his cab and deposit him in his yard.

One summer a tornado came through town. Really messed up Harry’s little yard. He’s ambling about in some ugly running pants trying to clean things up the morning after. I walk over and say, “Hey, Harry, you need some help?” So together for most of the day we haul branches and shit away and I mowed his grass. “How much do I owe you,” Harry says at the end of the day. I go, “Well… I dunno, it was sort of fun and really… I dunno…” Harry gets all red and says, “Jesus Christ, son! Don’t get all mealy mouthed on me!” I thought the top of his head would blow off. (What was left of it.) But, there you go. Writing Lesson One From Mr. Harry Crews: Don’t get all mealy-mouthed. (Son!)

Your poem “Hands” [reprinted at the end of this post] is one of our favorites. Can you talk us through your process of composition? What was the initial spark? How did the poem develop?

I revisit “Hands” and see how a poem can sort of conjure its own logic. And surprise, I hope. Like a lot of my poems, most even, “Hands” wants to be narrative and lyrical; associative, dissociative; a song and a story. I think the tension between all those camps can be powerful (sometimes) and I roll with it. A poem I’m writing can change gears and tone for me as long as it can cough up surprise. And an ending. But not shock. I’m the kind of guy who feels intuition and imagination trump idea, which is good because I don’t have any good ideas. Zilch. Nada. A conceit and sentimentality (Was it Oscar Wilde who said, “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling”?) really pisses on my poem parade.

Is there anything typical about the way a poem begins for you?

Many of my poems begin with something I recall, from when, you know, whenever. An image in the “Hands” case: A guy in a museum staring reverently at a painting. Nothing special. But I began writing from that (never about!) and caught a wave and went from there, but for a long time, never snagged an ending. The way I was writing it wasn’t taking the poem anywhere. As usual, kept revising, and, mercifully, like meditation, the longer you sit with something the intellect and all its nasty little rules get shouldered out by intuition, imagination and archetype; love and loss and God—you till the dark ground where the real world lives. The chit-chat chatter and that awful Journey song in your head die out and these other things insinuate and suggest themselves. Out of nowhere! Without order. That’s a bit, I think, of how “Hands” and many of my poems travel. But then again, I really don’t know what I’m doing. Which I like.

You’re from Florida but lived for a decade in Europe before returning to the American South. How did living inside a foreign culture and an unfamiliar language influence your work?

Yes, a decade in Holland. Ten years to the day! How about that. Five years in Amsterdam and five years in Abcoude, a medieval village a few kilometers outside of Amsterdam. (Here stands our Protestant Church! Built in 1455!)

I remember in my thirties leaving the South to do library work in Cambridge and later Berkeley. It was then I knew what it was to be a Southerner. And when I lived in Europe I never felt more American, whatever that is. I sense you have to leave a place before you really know it. Some might think it’s the same with people, but I’m not sure. The Zen boys say, “You get the map, but you don’t get the territory.” They’re talking about essence, of course, which can apply to place as easily, I think.

Being away from America for so long gave me, oddly, a clearer view of what the States can be all about. The good, the bad and the ugly. But Holland is a homogenous society, broadly speaking. I often felt I was meeting the same person, having the same conversion, inside the same house, eating the same food. I wanted to bitch and moan with my Dutch pals about all the sideways rain, or this or that perceived injustice, but these sort of things aren’t done. So there were frustrations. And lack of sun and, for me, metaphorically, warmth. Long stretches of time without hearing American blah-blah and sing-song made me read and reread a lot of American poetry. And it excited all my writing, greatly.

And this: I had a handle on some Dutch, especially understanding it and reading it. And I was not only writing features for Amsterdam Weekly [English language weekly] but also editing for them. Line-editing. I would get some pieces written in English from Dutch journalists and go through it and un-stilt it. More often than not, total rewrites. Arduous. The key was translating their intended voice to the edited version, or make-up one suitable to the story, if I couldn’t discern one to begin with. Many years of that. Editing and translating from a foreign language is priceless work for anyone interested in making poems, I think. I did a lot of stuff like that. Keeps your hand in the game.

If you were to pack your bags and leave again for ten years, what volumes of poetry would accompany you?

Someone wrote about Jerry Lee Lewis, “He doesn’t make records. He makes crime scenes.”

Here’s a baker’s dozen of crime scenes: (Okay. I lie. It might be two bakers’ dozens)

Elizabeth Bishop: The Complete Poems, 1927-1979

Kenneth Koch: Selected Poems (Ron Padgett, editor)

Ruth Stone: In the Next Galaxy

Rimbaud: Complete Works (Paul Schmidt, translator)

William Carlos Williams: In The American Grain

William Carlos Williams: Selected Poems (Charles Tomlinson, editor)

Laura Kasischke: Space, In Chains

James Tate: The Eternal Ones Of The Dream

Samuel Beckett: Every word in every play and novel is poetry. Example: “Moments for nothing, now as always, time was never and time is over, reckoning closed and story ended.”

Walt Whitman: The Portable Walt Whitman (Mark Van Doren, editor)

Charles Wright: The World of the Ten Thousand Things, Poems 1980-1990

Tomas Tranströmer: Selected Poems (Robert Hass, editor)

The Voice of Robert Desnos: Selected Poems (William Kulik, translator)

T. S. Eliot: Selected Poems

Frederick Seidel: Poems, 1959-2009

Wallace Stevens: The Palm at the End of the Mind

Faulkner: Every word. Poetry.

Baudelaire: The Flowers of Evil

Yeats: The Major Works (though late Yeats is what gets me)

Mary Ruefle: Trances of the Blast

The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson, & Issa (Robert Haas, editor)

August Kleinzahler: The Strange Hours Travelers Keep

Pierre Reverdy (Mary Ann Caws, editor)

Gerard Manley Hopkins: Poems and Prose

Hands / Michael Martin

I like to hide

them behind me

like I’m sneaking up

on a Delacroix.

I like to point to the back row

when the tuba nails it;

sprinkle living daylight

to prime the inverse relationship

at the edge of the pit;

move my queen to Atom or Idea,

and just be done with it.

I like to tighten my cummerbund,

tip the tux;

hold the gold pan down deep

in the creek

’cause the square root of loss is pretty

much more of the same,

though the Penguin Hemisphere

keeps slipping through my fingers.

I like to hide a dime in a glove

and wave for mercy;

yet there’s always a risk of taking

the fabric out too soon,

but that’s the life of the hand for you.

After my friend’s daughter

died he began building

one of those stone walls

you see all around New England.

This particular wall

only went shoulder high

because my friend could

never lift the heavy rocks

higher than his two grieving shoulders.

A mile of shoulder high wall

built by Suffering Man.

You see it everywhere.

Hushed, meandering line.

Border around everything left.

It took my friend forever

to build it, which, he said,

was fine by him.

Portals Press, 2015. Reprinted with permission.

extended remark, which we highly recommend, is available from your local bookshop, Portals Press, Amazon, and all the places good books are sold.

Michael Martin has several upcoming poetry readings:

Quail Ridge Books, August 25th, 6 p.m.

Kinston, NC, Public Library, Sept 19th, 3 p.m.

Latter Library, New Orleans, LA, Oct 3, 2 p.m.

Maple Leaf Bar, New Orleans, Oct 4, 3 p.m.

* To receive notifications of new posts, please sign up via our contact page with the subject "Subscribe."