Some firsts stain our imaginations like watermarks. For instance, those unforgettable firsts in a reader’s life: the initial taste of Colette or Bohumil Hrabal or one of those non-related Zweigs, Stefan or Paul. The experience, say, of a film by Tarkovsky or Angelopoulos, directors who make us understand—much as we understand the first time we hear Patti Smith’s “Free Money”—all the ways that an artist can at once define and exhaust the possibilities of a form. We never forget the charge of these moments.

“[A] great work of art is of course always original, and thus by its very nature should come as a more or less shocking surprise,” Nabokov writes in the foreword to Lolita. With this in mind, the reader develops an urge to move always to the next surprise, the next score. We get our hit, and we want more.

“I’m off balance, not sure what’s wrong,” Patti Smith writes in her new memoir, M Train. She’s made a pilgrimage—one of many in this book by someone who regards literature as a religion, and artists and creators as idols—to a statue of Nikola Tesla.

“You have misplaced joy,” the ghost of Tesla informs her. “Without joy we are dead.”

“How do I find it again?” Smith asks.

“Find those who have it and bathe in their perfection,” Tesla says.

Smith inhabits many lives. For some, she’s the Priestess of Punk, for others a poet who speaks to her generation and beyond. Then there’s her other, more recent role, that of National Book Award-winning author. With M Train, her highly anticipated follow-up to Just Kids, Smith offers us a book that is both gift and education. These pages are a hymn to reading. Names of her hero literary renegades course through them: Jean Genet, Mohammed Mrabet, Paul Bowles, Gérard de Nerval, Albertine Sarrazin and Roberto Bolaño.

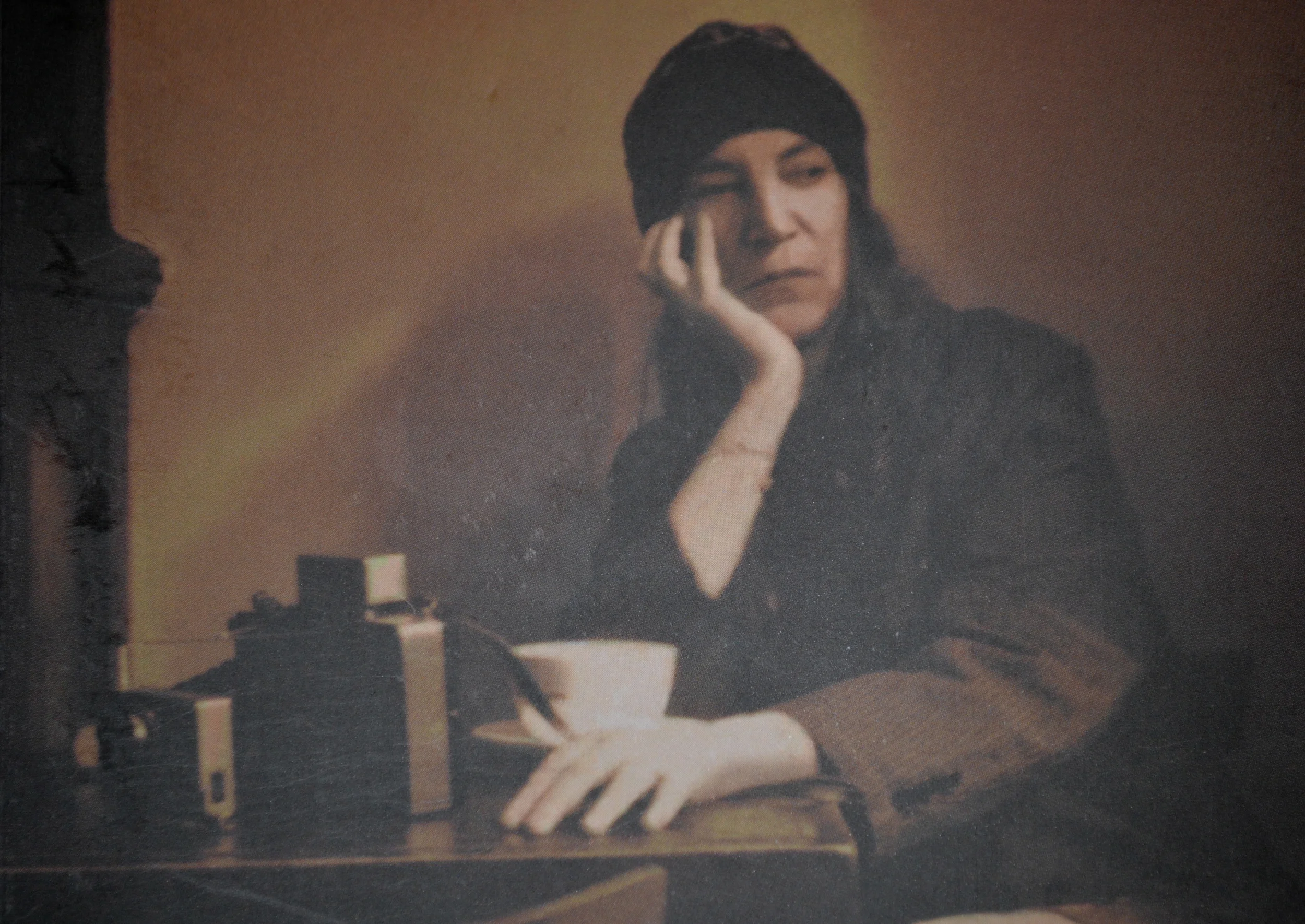

A singer with the stage presence of a cult leader, Smith also has a solitary soul that makes her elusive, someone whose imagination and promiscuous reading allows her to move through life like a flâneuse even when she’s sitting still in one of her favorite cafés.

These pages, therefore, bestow another title on Smith, that of reader’s reader. As a child, she identified with the American frontiersman and soldier Davy Crockett, whose story she discovered as a second grader browsing library shelves. Crockett’s deportment may have helped to instill Smith with an “inbred cockiness,” but the Patti Smith enigma includes a self-defined “abundance of romantic enthusiasm.”

The woman whose albums include Horses, Dream of Life and Banga finds herself most comfortable alone at her regular café table, lingering over coffee and a book. When not there or seeking more coffee (there’s plenty of caffeine abuse here), Smith moves through the streets like a junky: “I walked east to St. Mark’s Bookshop, where I roamed the aisles, randomly selecting, feeling papers, and examining fonts, praying for a perfect opening.”

In London, she buys a copy of The Master Builder and reads it in front of the fireplace in the hotel library.

“Hmmm,” says another guest, “lovely play but fraught with symbolism.”

“I hadn’t noticed,” Smith says before examining her philosophy as a reader: “Why can’t things be just as they are? I never thought to psychoanalyze Seymour Glass or sought to break down ‘Desolation Row.’ I just wanted to get lost, become one with somewhere else, slip a wreath on a steeple top solely because I wished it.”

Later, she attempts to understand the great books that have moved her and why they do so. “There are two kinds of masterpieces,” Smith writes:

There are the classic works monstrous and divine, like Moby-Dick or Wuthering Heights or Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus. And then there is the type wherein the writer seems to infuse living energy into words as the reader is spun, wrung, and hung out to dry. Devastating books. Like 2666 or The Master and Margarita. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is such a book.

Of the latter, Smith writes, “For one thing, I did not want to exit its atmosphere.” She continues this thread for a few pages and then comes upon another readerly realization: “The truth is that there is only one kind of masterpiece: a masterpiece.”

Early in M Train, Smith writes of another favorite, W.G. Sebald, and his posthumously translated first book, After Nature: “What a drug this little book is; to imbibe it is to find oneself presuming his process. I read it and feel the same compulsion; the desire to possess what he has written, which can only be subdued by writing something myself. It is not merely envy but a delusional quickening in the blood.”

M Train has a similar effect. Expect to see copies of it in the hands of commuters and readers in cafés. And don’t be surprised if, before long, you notice a proliferation of After Nature, the works of de Nerval, Isabelle Eberhardt and the many other overlooked authors to whom Smith pays homage, further watermarks awaiting readers who will now discover them thanks to these delightful pages.

KR

You can find Patti Smith's M Train at Avenue Bookstore and at all good bookstores around Australia, and at Powell's and at your neighborhood bookstores in the United States (Try Maple Street!).

Listen to Tom Ashbrook's On Point interview with Patti Smith about M Train here.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, contact us with the message "Subscribe" or follow us via our Facebook page.