With the arrival of spring in the Southern Hemisphere, we find ourselves thinking about Pablo Neruda, whose poem “Every Day You Play with the Light of the Universe” has always been one of our favorites. Here’s that wondrous ending in W. S. Merwin’s translation:

I want

to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees.

Eighty years ago, in 1936, Neruda served as Chile’s consul in Madrid. That same year, he witnessed the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. In the early days of battle, you could reach the front lines by tram.

“Time passed,” Neruda writes in his Memoirs. “We were beginning to lose the war. The poets sided with the Spanish people.” One of them, Neruda’s friend Federico García Lorca, was murdered within weeks of the war’s outbreak.

Neruda responded to the country’s civil war with the poems in Spain in Our Hearts, or what he called “my book on Spain.” The story of the book’s printing and survival deserve their own lengthy odes. So, too, does Manuel Altolaguirre, the man who set up a press on the eastern front, where he printed España en el corazon (1937).

In his Memoirs, Neruda describes Altolaguirre’s unusual process:

The soldiers at the front learned to set type. But there was no paper. They found an old mill and decided to make it there. A strange mixture was concocted, between one falling bomb and the next, in the middle of the fighting. They threw everything they could get their hands on into the mill, from an enemy flag to a Moorish soldier’s bloodstained tunic. And in spite of the unusual materials used and the total inexperience of its manufacturers, the paper turned out to be very beautiful.

By the time copies of the book became available, the Spanish Republic’s defeat appeared imminent. Hundreds of thousands of refugees began their long march out of the country.

Among those on the packed roads were Manuel Altolaguirre and some of the soldiers who printed España en el corazon. “I learned that many carried copies of the book in their sack, instead of their own food and clothing,” Neruda writes. “It was the exodus, the most painful event in the history of that country. … That endless column walking to exile was bombed hundreds of times. Soldiers fell and the books were spilled on the highway.”

After the war ended in 1939, Altolaguirre, also a poet, continued to publish his own work and that of others. He died after suffering injuries during a car accident twenty years later. When Neruda received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971, the Swedish Academy cited his time in Spain as the “turning point” in his work: “It was as if a release from the shadow of death and a way towards fellowship were opened when he saw friends and fellow writers taken away in fetters and executed.”

The book that Altolaguirre published has become, as Neruda notes, truly rare. “The few copies [of España en el corazon] still in existence produce astonishment at its typography and its mysteriously manufactured pages,” he writes in his Memoirs. The work itself, so different from what we find in Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair or Elemental Odes, produces in the reader a passion for Spain and an anger for the war that, unfolding on the eve of one even more monstrous, has become—for too many—a footnote in the long list of the century’s crimes.

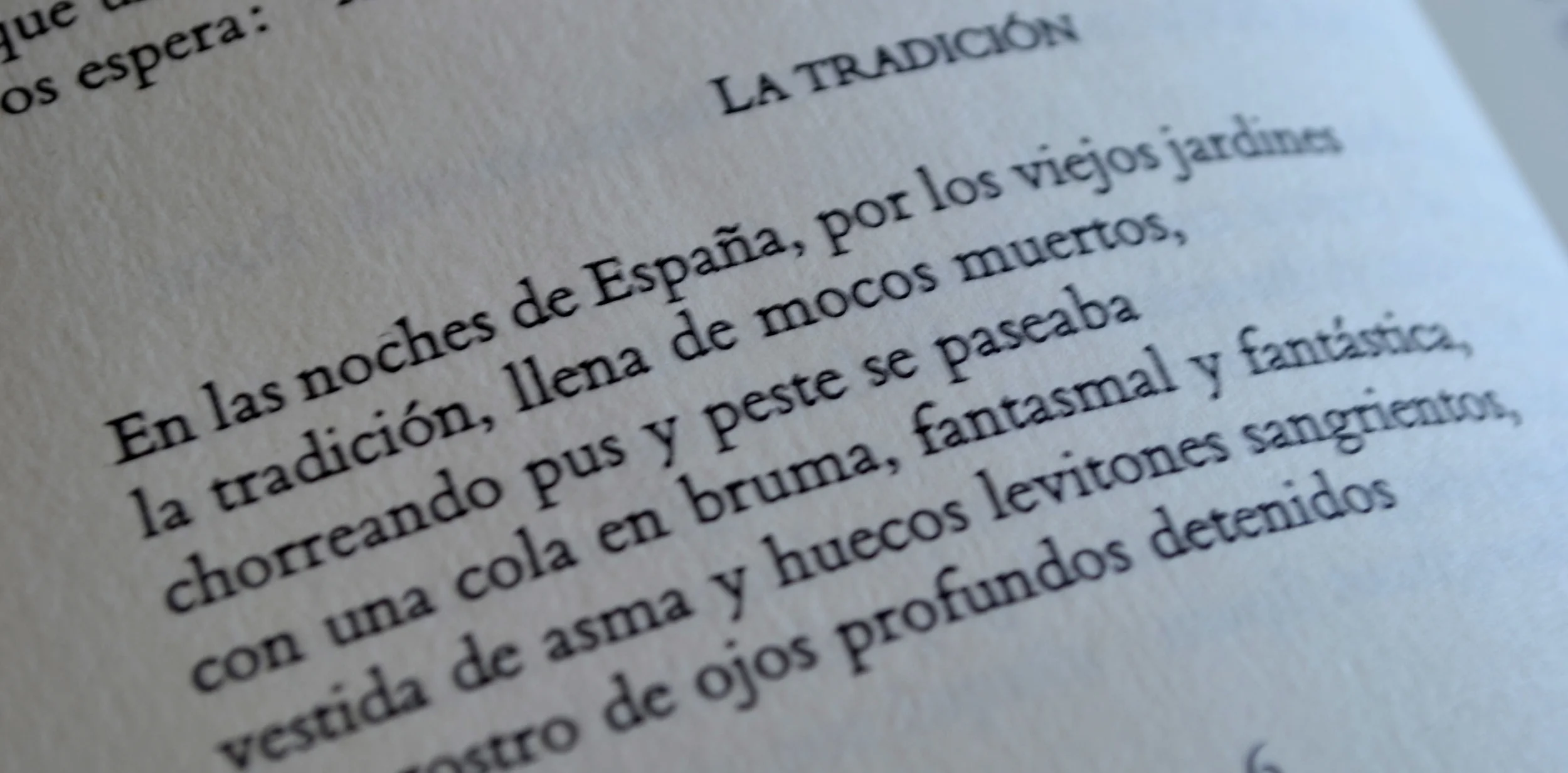

From “I Explain a Few Things,” published in Spain in Our Hearts:

You will ask: why does your poetry

not speak to us of sleep, of the leaves,

of the great volcanoes of your native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets,

come and see

the blood in the streets,

come and see the blood

in the streets!

KR

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe here or follow us via our Facebook page.