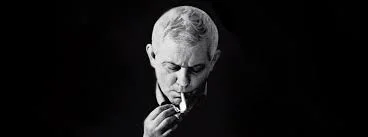

Photo: Detail of book jacket art from The Collected Poems: 1956-1998 by Zbigniew Herbert, photograph by Anna Beata Bohdziewicz

.

By Kevin Rabalais

It’s inevitable. Every time I walk into a bookstore, I find myself longing to buy stacks of books—and I don’t mean stacks of just any books. My great desire has always been to leave the store with copies of books that I already own. I want reading copies. I want pristine copies. I want editions with different introductions, American editions, English editions, French editions. Then I want a few more copies just in case, the kind to give away when the right reader comes along.

There are, I’ve been told, worse crimes, so for now, I’m going to keep feeding the habit. After all, if you have the choice between books and food, buy books, since your friends are more likely to feed you than to support your addiction.

“My life is littered with copies of Moby-Dick,” Peter O’Toole says in an interview with Gay Talese. The idea seemed visionary when I first read it. And it still does, twenty years later, though now I’m willing to admit that I may have misread O’Toole’s devotion to Melville as drunken mis-remembrance of what he already owned. Whatever the case, from that statement I carved out precisely what I needed to hear. I read it like a blueprint on how to live. Fill your life and your surroundings with what you hold dearest. Let what nourishes you be apparent in your daily existence. Assemble your time on this planet so that you live in the throb of what sustains you most, for this material—art, music, literature—becomes the lens through which we experience the world.

If it isn’t obvious by now, these are the notes of a privileged life, for by definition, at least in my worldview dictionary, all readers live a privileged life.

At the end of last year, I experienced one of those luxurious moments that I often find myself daydreaming about. Looking back, two months later, it still makes me envious. I was in another city (Sydney), in one of that city’s best independent bookstores (Berkelouw Books: three stories, new and used!), with the gift of a full hour at my disposal. I had nothing to do—no appointments, no concerns—but to browse the shop’s abundant shelves. Any reader knows the sensation. It feels like an assignation.

I began in the literature section. Then, before I made it out of the B’s, the old problem presented itself. How would I get those copies of Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers, The Unknown Quantity and The Death of Virgil home without any checked luggage? I’d need to buy another bag. Or, given the twenty-four letters left in the literature section alone, maybe I’d need two.

Thinking geographical distance might help me ponder these drastic decisions, I moved upstairs in search of the poetry section.

Spotting an edition of a favorite writer’s work on the shelf—even an edition that you’ve never seen before—can feel a bit like love at first sight. This one was silver and slim, with black and blue type on the spine and one of those nostalgically comforting 1980s covers. For years, I had carried around quotes by the writer, one of the brightest stars in that constellation of twentieth-century Polish masters. I had always thought of him as guide and master.

Fittingly, the book opened to a poem titled “Old Masters.” I read these lines:

I call on you Old Masters

in hard moments of doubt

—Zbigniew Herbert

We can’t hold all of Anna Karenina or The Iliad in our memory. And yet from those works lingers an essence, the climate of the book that we crawled around and lived inside for days or weeks. That climate saturates our lives. On the shelves of libraries and bookstores, we see copies of the books we’ve read, the ones that changed us, the ones that saved us. At once it all comes back, a recognition of who and where we were when we lived—however briefly, however fully, however hopefully—inside that master’s world. Through our days, we carry lines with us, lines that return at unexpected moments. We find ourselves calling on them, those masters we keep close, in our times of need. Herbert was one of mine, and here we were, together again on the third floor of Berkelouw Books.

A brief historical note: I found myself browsing the shelves of Berkelouw Books in late 2016. You would be forgiven for thinking, as late as mid-2016, that it would have taken Kafka and Melville and Huxley and a parliament of fantasy and dystopian writers to imagine the events that unfolded in the final gasp of that year, but here we are. In this era that seemed nothing short of desperate (how could civilization survive? how could we go on after this?), I needed Herbert’s wisdom, but my copy of his 624-page Collected Poems was a continent away, and now I had found him again in this simple but elegant Ecco Press edition of Report From the Besieged City. I needed Herbert (1924-1998) to show me what he knew. I needed him to tell me how he survived what he witnessed—as a Polish man, as a human—who lived through some of the darkest periods of his own century.

The poems in Report From the Besieged City were originally published in 1983 by internees in Warsaw’s Rakowiecka Prison. As John and Bogdana Carpenter write in the introduction to the Ecco edition, almost all of the copies were eventually confiscated. And yet Herbert continued to write; his work continued to be circulated, often through the underground press.

I can think of few writers who, with a single line, give us reason to go on.

Lord

I thank You for creating the world beautiful and very diverse

…

—forgive me also that I didn’t fight like Lord Byron for the happiness of captive peoples that I watched only risings of the moon and museums

…

permit that I understand other people other tongues other sufferings

and above all else that I be humble which means he who desires the spring

thank You Lord for creating the world beautiful and diverse

and if it is Your seduction I am seduced forever and with no forgiveness

—“Prayer for Mr. Cogito—Traveler”

I didn’t think twice about leaving Berkelouw with Report From the Besieged City. I’ll keep it close, along with that old notebook that contains the following lines from Herbert’s “Five Men”:

thus one can use in poetry

names of Greek shepherds

one can attempt to catch the colour of morning sky

write of love

and also

in dead earnest

offer to the betrayed world

a rose

The end of 2016 felt like the beginning of a new betrayal, one that Herbert didn’t live to witness but that he would have understood. “[A]nd only our dreams have not been humiliated,” he reminds us in the final line of Report From the Besieged City. It is enough, this need to cling to those dreams, to keep faith that we are and can be better than this.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.