By Kevin Rabalais

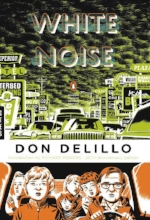

“It’s the day of the station wagons,” says Jack Gladney near the beginning of Don DeLillo’s 1985 National Book Award-winning novel, White Noise. “I’ve witnessed this spectacle every September for twenty-one years. It is a brilliant event, invariably.”

Gladney teaches at the College-on-the-Hill. Each fall, at the start of the new school year, he walks to campus to watch the students return from summer break. There, behind the dark glasses that he wears while strolling through the quads and inside the classroom, Gladney gauges the social status of parents and catalogues the students’ possessions: “the stereo sets, radios, personal computers; small refrigerators and table ranges; the cartons of phonograph records and cassettes; the hairdryers and styling irons; the tennis rackets, soccer balls, hockey and lacrosse sticks, bows and arrows; the controlled substances, the birth control pills and devices; the junk food still in shopping bags…”

Little escapes Gladney’s notice in this novel, one of the funniest and most horrific in contemporary American fiction. Founder and sole member of the Department of Hitler Studies, Gladney lives in fear that someone will discover he has scant comprehension of the German language. His obsession with Hitler has led to an obsession with death; he and his third wife, Babette, spend many conversations arguing why each should be the one to die first. Despite these and other foreboding topics, DeLillo makes us laugh out loud for much of this novel that chronicles, among many subjects, family life in late twentieth-century America.

“The family is the cradle of the world’s misinformation,” DeLillo writes. “There must be something in family life that generates factual error. Overcloseness, the noise and heat of being. Perhaps even something deeper, like the need to survive.”

Each September, as American universities reopen their doors for the start of the new school year, I think of Gladney’s fascination with “the day of the station wagons.”

This year, a reread of White Noise lured me back to the new semesters of my own university years. DeLillo reminded me of what became, in those years, a favorite pastime: the spectacle—“the brilliant event, invariably”—of browsing the books on the syllabi for other students’ courses.

College, if it has any definition, might very well be that place where one reads serious books. For any reader, the start of a new semester seems miraculous. Serious books line the bookstore shelves, grouped under Economics and English, Biology and Mathematics, Religion and History. The list goes on, shelves filled with books selected by experts in their fields. I always found it a privilege to browse those offerings. Doing so reminded me of the significance of the university, that great institution which entrusts men and women with the enviable job of shaping young minds and directing students toward readings that will help them think more thoughtfully and become capable of expressing those thoughts clearly, perhaps even eloquently.

A lifelong discomfort in the company of numbers means that most of the serious books I wanted to read were in the “English” section. I spent my time hunting the truths that certain Southern ladies (thank you, Ms. Welty and Ms. O’Connor) convinced me we find in the beating heart of fiction. I wanted characters. I wanted to feel the climate of places I hadn’t had the chance to visit and maybe never would. I wanted emotional history. I visited the bookstore shelves to find them. I bought books for classes that I couldn’t take. They were on the syllabi: they had to be important.

One of those books, Tolstoy’s novella The Forged Coupon, excited me so much that I bought an extra copy and gave it to my father. This was college, and he was still footing the bill, but a gift is a gift and we’re talking about Tolstoy. Several weeks passed before I heard a fellow student enrolled in that class complain that the bookstore hadn’t ordered enough copies so she couldn’t complete her reading assignment. I managed to stay quiet and only sometimes feel guilty about it.

The Forged Coupon follows precisely what its title suggests. The novella begins when one character in need of money requests a loan from his father. After being turned down, he asks a friend for help. That friend forges a note. He then suggests they break the note by passing it off on an unsuspecting shopkeeper. When the shopkeeper’s husband discovers what his wife has done, he calls her a fool. To rectify the financial loss, the husband passes the forged note on to the man who sells them wood. And that’s only the beginning. If anyone still has a doubt that fiction holds the power to shake us alive, reminding us that our actions—good and bad—affect others, and that the art of the novel has the potential to show us how to live among others in this world, take a look at Tolstoy.

I can’t remember which professor used The Forged Coupon in the classroom. All I remember is wishing that I could sit in on those discussions. But there were other books on my own syllabi, many of them unforgettable, the kinds of books that mark that golden age in a reader’s life when everything is new and we’re still convinced there will be enough time to read everything. As Conrad reminds us, however, life is short and literature is long. Being aware of the abundance, all of those worlds on bookshelves awaiting our arrival, is one of the great privileges of the reading life.

After browsing—and often buying—I’d go back to my dorm. At Loyola University New Orleans, a Jesuit lived on every floor of our building. I lived a few doors down from a wise one (is there any other kind of Jesuit?) who made pots of jambalaya that I still dream about. We assembled around him in the communal kitchen.

“Don’t get complacent with that onion,” he said after requesting my help. No one will ever convince me that his directive wasn’t a metaphor.

The Jesuit who lived upstairs we respected and feared. At night, passing by his always-open door, you could hear the steady hum of his old typewriter. From it spawned the pages that eventually became his book on the great journalist Eric Sevareid, one of “Murrow’s boys,” the latter detail a single grain of knowledge he imparted with grace and generosity. His uncle had edited the Brooklyn Eagle, a position that Walt Whitman once held. We had seen this Jesuit at work, two gloved fingers drumming the keys as the elegant pages piled high. On that growing stack, my friends and I were shocked to see that the margins of his crystalline prose contained as many corrections as the papers he handed back to us. Over impossibly strong black coffee and undrinkable Merlot, we nibbled on his favorite snack, peanut butter spread thickly on Ritz crackers, eager for him to anoint us in the meaning of life.

“You don’t speak enough in class,” he said to me one night. “You’re not presenting your ideas.”

To get the peanut butter down, I had no choice but to drink the syrupy coffee, now long cold. “I don’t always get a chance,” I said.

“You must formulate your ideas. You must express yourself. If you don’t, who will you become?”

Word by word, line by line, he read my work and offered guidance. In several of Richard Ford’s Bascombe novels, he appears as Fr. Ray. For every paragraph I write, all these years later, I feel his breath on my neck. “It’s not there, not yet,” he says, shaking his head.

“You must formulate your ideas. You must express yourself.

If you don’t, who will you become?”

A few years ago, I received a phone call from a young woman requesting that I make a financial contribution to my alma mater.

Loyola has always been good to me, I said. I then apologized and explained that, although I wished things were different, I couldn’t offer anything that year.

A pause on the other end of the line, a shuffling of pages, and then the sound of that voice, enviably young and certain: “Oh, now I see why you can’t afford to give any money. You were an English major.”

Yes, I said, remembering the story about how Tolstoy could walk into a room and know everything about everyone in under ten minutes.

Tolstoy and DeLillo, those two Southern ladies, the Jesuits and a lifetime of reading: all of this has taught me to look both ways and then to look again. They have taught me about all the layers that we fail to see unless we stare intensely and question and then question some more, and that people and things are never as simple as they seem.

And for that questioning and searching and the desire to comprehend, I offer thanks and no apologies.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.