By Kevin Rabalais

When the Viennese author Stefan Zweig first travelled to Brazil in 1936, he deemed the South American country “terra incognita in the cultural sense.” The former Portuguese colony had once been unknown in the geographical sense, as well, this “land that one should hardly call a country anymore,” as Zweig wrote in Brazil, “but rather a continent.”

There I was confronted not only with one of the most magnificent landscapes on earth—that unique combination of sea and mountains, city and tropical nature—but also with a completely new kind of civilization.

All great literature forces us to confront what is in front of us. One of the wonders of reading, of course, is that what we confront may be centuries or hemispheres away. We read and rethink. We read and correct our prejudices and stereotypes.

“For many years Jorge Amado tried and knew how to be the voice, the feeling, and the joy of Brazil,” José Saramago writes in his introduction to Amado’s delightful (and delightfully titled) The Discovery of America by the Turks. This slim novel, recently translated into English for the first time, follows two Arab immigrants who arrive in Brazil in 1903. In this novel filled with gunslingers, merchants and a love affair on the frontier, Amado delivers his story with characteristic wit. Early on, he writes of Raduan Murad, “a fugitive from justice for vagrancy and gambling, a scholar with seductive prose”:

Raduan Murad was imaginative, inventive, and as far as scruples were concerned, he cultivated none at all. … Truth or trick? … It is better to concern ourselves with proven, undeniable facts, even though the truthful story does touch upon the miraculous.

In recent years, Penguin Classics has reissued several novels by Amado, who until now been best known for Garbriela, Clove and Cinnamon and Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands. Besides The Discovery of America by the Turks, these new editions include The Violent Land, Captains of the Sands and The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray.

Saramago writes of what the publication of this work has meant and continues to mean to non-Brazilian readers:

The generalized and stereotyped picture to which Brazil had been reduced, to the sum of white, black, mulatto, and Indian, was now being progressively corrected, albeit in an unequal way, by the dynamics of development in the multiple sectors and social activities of the country, and has received in the works of Amado a most solemn and at the same time delightful disavowal.

Worth tracking down, Lêdo Ivo’s novel Snakes’ Nest, or A Tale Badly Told takes place during the “New State” of Brazil that lasted from 1930 to 1945. It’s the kind of novel that Faulkner might have written had he been born on the east coast of Brazil, focused on his poetry and been forced to live through fascism and then a dictatorship. Ivo’s allegorical novel unfolds in the voice of a seductive yet unreliable narrator* who relates the intertwined fates of the characters living in a semi-fascist state as they work out their understandings of good and evil. Many of their conversations revolve around a fox that has ventured from the wilds into the heart of the city.

“Like all animals,” writes Ivo, “she didn’t believe in her own death; she judged herself immortal, even though she accepted her immortality with the bland indifference of a being without metaphysics.”

These characters live in a violent and corrupt land, and Ivo calls his novel, originally published in 1973, “a story of terror and violence that is, surely, a sunny nightmare.”

In 2012, Granta named Michel Laub and Tatiana Salem Levy among its list of Best Young Brazilian Writers. Both have recent novels translated into English. With its incessant investigation of the nature of storytelling and the process of creation, Levy’s The House in Smyrna recalls the radical work of Clarice Lispector.

“To write this story, I must leave here and go on journeys to places I don’t know, lands in which I have never set foot,” Levy writes in this novel about a woman in Rio whose grandfather challenges her to travel for the first time to the home the family left behind in Smyrna.

Another family story, Laub’s Diary of the Fall—the first of his five novels to be translated into English—proves that there are still new ways to write about Holocaust survivors. The novel centers on a prank that a group of Jewish students commit against the sole Catholic classmate at their elite Rio school. This family story unlike any other leaves us longing for further translations of Laub’s work.

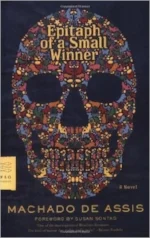

And to end with the great Brazilian writer Machado de Assis, whose Epitaph of a Small Winner gives us one of our favorite opening paragraphs in fiction:

1. The Death of the Author: I hesitated some time, not knowing whether to open these memoirs at the beginning or at the end, i.e., whether to start with my birth or with my death. Granted, the usual practice is to begin with one’s birth, but two considerations led me to adopt a different method: the first is that, properly speaking, I am a deceased writer not in the sense of one who has written and is now deceased, but in the sense of one who has died and is now writing, a writer for whom the grave was really a new cradle; the second is that the book would thus gain in merriment and novelty. Moses, who also related his own death, placed it not at the beginning but at the end: a radical difference between this book and the Pentateuch.

For the past few weeks, the world’s eyes have turned to Brazil, a land that has retained its cultural exoticism. These writers help us chart new borders, bringing us closer to comprehending the terra incognita that Zweig discovered eighty years ago.

*Ivo: “Regarding the figure of the unreliable narrator, I think it is true that during a dictatorship, all narrations are poorly told, since a dictatorship is the Kingdom of Lies and cannot tolerate the truth. How can one tell the truth or tell a truthful story in a regime of terror, persecution, and the destruction of the individual.”

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.