By Jennifer Levasseur

More than once, friends and acquaintances have told me that they do not see the point of reading fiction, that if they make (or find) the time to read, it’s history or biography: real life, facts, things that aren’t made up, things that will teach them something. While I understand the draw of great histories, life stories, the kind of nonfiction that explores an obscure figure or process or object (think Einstein’s Brain or Salt or Stiff), I’ve never understood why readers feel the need to plant a flag in a particular camp, why some view fiction as unnecessary and frivolous, the equivalent of silly TV sitcoms or forgettable movies you’d only watch on a long-haul flight.

I tend to prefer, perversely, fiction that makes me uncomfortable, novels that force me to question the choices I’ve made, stories that remind me that I am the center—only—of my own tiny universe and that many other universes bump into mine and are influenced by mine, just as mine takes hits from all of theirs. Some of my favorite novels unnerve me. They make me want to take to bed for days. Or to march in the street to overthrow every wrong. They often do teach me things. I love historical novels that put me in the shoes (or bodices) of Victorian prostitutes or of settlers making first contact with Aboriginals in Australia, or of everyday Germans living out the Second World War in quiet despair. While these characters may be invented, they are not make-believe. They are born of truth, and their (fictional) lives spread truth. They allow us many other lives. They let us visit other planets. But not like astronauts on foreign worlds viewing the other. More like embodying the alien, living its life, feeling its particular desires and failures.

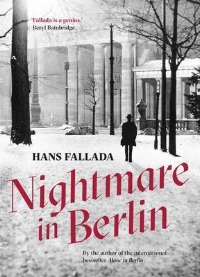

I didn’t want to read Hans Fallada’s recently translated 1947 novel, Nightmare in Berlin, but I felt compelled to do so. Semi-autobiographical and written shortly after the end of the war, Nightmare in Berlin follows an ordinary man (a writer) and his wife who hunkered down in Germany during the war, hoping for the best and fearing the worst. They did nothing to aid the war effort, but they did nothing to oppose it. They never joined the party, but they went on with their lives, scrambling for food when the supply ran short, comforting each other, waiting for change. When Russian troops roll in, the wife runs out to welcome them.

But the collective guilt remains strong. Is it enough to claim that he had no power, no influence? Is he forgiven because he spent part of the war in a mental facility and briefly in prison, that he only pretended to write anti-Semitic texts to protect himself? Should he have sacrificed his life? But in what way? What could his little life have done to influence anything?

And, now, that he and his fellow citizens are starved, dressing in rags, traumatized and sick, what can he do? What should he do?

It’s easy, from this distance and with moral superiority, to denounce the character and Fallada for his silence, for the fact that he remained in Germany instead of fleeing (which becomes a kind of complicity), for having lived and then turning to morphine to dull the terror of the future and the past, for changing the end of his 1938 novel Iron Gustav under pressure from the Nazi Party (he continued the action of the novel through the 1930s and had main characters shake hands with senior Nazi officers). Fallada himself stayed in Germany, struggled with his drinking and decided to continue working on “a quite unpolitical book which can’t give offense.”

“The author of this novel is far from satisfied with what he has written on the following pages, which is now laid before the reader in printed form. When he conceived the plan of writing this book, he imagined that alongside the reverses of everyday life—the depressions, illnesses, and general despondency—that alongside all these things which the end of this terrible war inevitably visited upon every German, there would also be more uplifting things to report, signal acts of courage, hours filled with hope. But it was not to be.”

As Geoff Wilkes writes in the afterword of Alone in Berlin, “There is no simple concept which adequately describes Fallada’s career in Nazi Germany: he was neither an eager collaborator nor a resistance fighter.” He accepted commissions, his son joined the Hitler Youth, but he also defied their ideals in his novels such as Wolf Among Wolves. Wilkes summarizes his difficult position thus: “It is not overly generous to point out, however, that what resistance he made put him in actual, deadly jeopardy, and what compromises he made were in the same context.”

It’s most uncomfortable because Fallada (and his character) is us. What do we do when horror strikes? Whether it’s a terrorist attack or a police shooting (by them or at them) or casual racism or institutionalized racism or hate-spewing politicians or xenophobia—do we do more than pause for a moment, shake our heads, then go to work or make our lunches or see a film? Should we? If so, what? Is it enough to vote, to enact small, everyday kindnesses, to love people unlike us? To march in the street?

I don’t know. And Hans Fallada—both himself and his fictional alter ego of Nightmare in Berlin—didn’t know. So he woke up every morning in despair and went to sleep in despair and dulled himself with drugs in between. Eventually, he pulled himself together and tried again with the only instrument he had: his writing.

Though Fallada died in 1947, he wrote one more novel. Translated into English as Alone in Berlin or Every Man Dies Alone, it offers an alternate version to the one described in Nightmare in Berlin. Set in 1940, an ordinary German couple is disgusted by what their country is becoming. They have tried to be faithful citizens, and they welcomed a leader whom they thought would save their country from financial ruin. Their only son, sent off to fight, is killed at the front and they begin to question what they have accepted. They have little but each other and their outrage. Though they know their voices are weak and their real influence insignificant, they make the most daring gamble. They begin to drop anti-Hitler, anti-Nazi postcards around the city in an effort to turn public opinion against the Reich. They expect little response, and they know if they’re caught they are likely to be tortured and killed. The effort, while seeming so pitiful (what is a postcard that one or maybe a dozen people will see and disregard with fear or turn in to the Gestapo?), puts them in grave danger. They will not plod along even if their defiance will do little but kill them.

Fallada’s life—but even more so, his novels—leave me unsettled and on the verge of despair, even with their glimmers of hope. That despair is important; it’s necessary. It reminds me that I have to do more than wake up, go to work, hug my friends, entertain myself.

I—we—have to do more, even if that more is as pitiful as postcards—or an article—that few ever read. The act of doing it is little, but it is a little something and that something must always be better than nothing.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.