By Kevin Rabalais

In a few weeks, against all odds, Brazil will try to present itself as “the land of the future,” as Stefan Zweig deemed it after his 1936 visit. Using that phrase as his title, Zweig wrote a book about the country whose culture felt to him like “terra incognita.” It felt much the same way—almost like another planet, it seemed—to many filmgoers who first glimpsed São Paulo in the 1985 film version of Manuel Puig’s novel Kiss of the Spider Woman. And now, with ongoing fears of the Zika Virus, bacteria in the waters, infamous crime rates and images of men at Rio’s airport holding signs that read “WELCOME TO HELL: POLICE AND FIREFIGHTERS DON’T GET PAID, WHOEVER COMES TO RIO DE JANEIRO WILL NOT BE SAFE,” Brazil feels less comprehensible than ever.

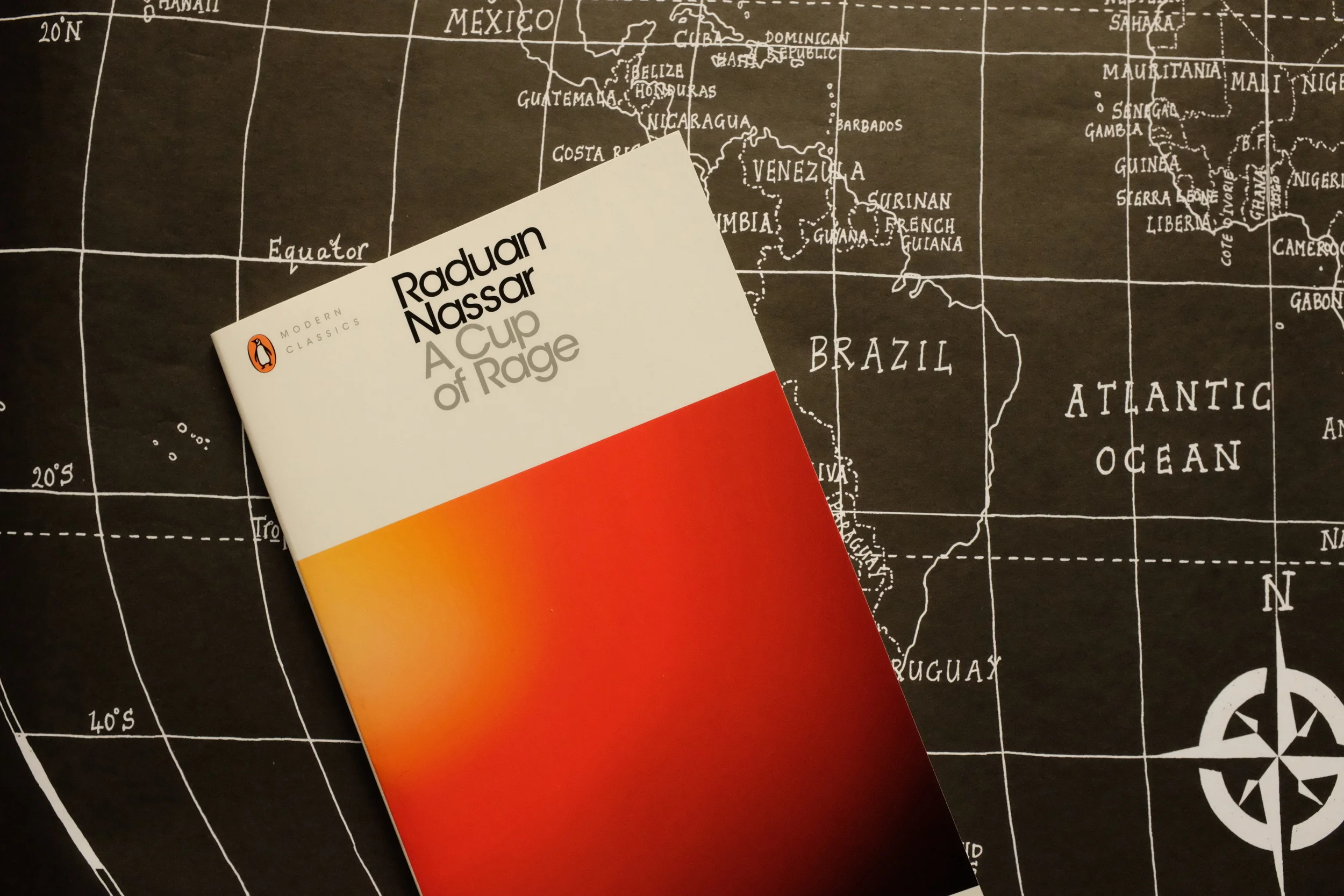

In the lead-up to this year’s Summer Olympics, we’ve seen a rise in books about Brazil, including Alex Cuadros’s Brazillionaires, about the country’s recent boom and consequent rise in wealth, Misha Glenny’s Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio and Luis Eduardo Soares’s Rio de Janeiro: Extreme City. Earlier this year, Penguin Modern Classics published Brazilian novelist Raduan Nasser’s experimental and confronting novella, A Cup of Rage. Told in seven chapters, each comprised of a single, intricate sentence, it follows the owner of an isolated farm and his younger lover, a journalist, as they meet, make love, have breakfast and then proceed to try to dominate, be dominated and destroy one another emotionally.

That longest of these chapters, “The Explosion,” runs thirty pages. Nasser nearly stops time altogether as the two characters argue while the farmer notes his lover’s “viper’s tongue,” referring to it as a “well-oiled instrument” while he wonders whether “she had really got to me, or was I rather, an actor, only faking, to follow an example, the pain that I really felt….”

With his rococo prose and this latter observation, Nasser connects himself to the widespread experimentation that began in Brazilian fiction with the “Generation of 1945,” group of writers who rejected modernism and worked in highly stylized prose. (In the coming weeks, we look forward to focusing on the most widely translated of these writers, Clarice Lispector, whose Complete Stories also has been published recently by Penguin Modern Classics.) The rewards here, as in much of the work of these playful and stylistically acrobatic Brazilians, stems not so much in what happens but in how it unfolds. A Cup of Rage is one of those taut works of fiction in which everything (go figure) actually counts and the reader finds that the true narrative (to borrow from Conrad) begins only after we finish these breathless sentences.

While Nasser allows his two main characters to present their fears, desires and everything they hate about themselves and one another, he seems to have taken Edgar Allan Poe’s theory of short narratives as a challenge. “If any literary work is too long to be read at one sitting,” Poe wrote, “we must be content to dispense with the immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression.” The form here proves necessary for Nassar to convey his characters’ emotions and the rage of his title. His long sentences produce a near-physical effect in the reader, heightening its complexity until the chilling final chapter of this forty-five-page novella by a novelist deemed one of Brazil’s “most infamous modernist writers.”

In the coming weeks, as we try to understand the country that is, as Zweig wrote, “terra incognita in the cultural sense,” we look forward to brushing up on more Brazilian literature. As always, we will offer regular updates about our discoveries. We hope that you continue to do the same.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.