Painting of Fernando Pessoa by José Sobral de Almada Negreiros, Casa Fernando Pessoa

By Kevin Rabalais

What do I know? What do I want? What do I feel? What would I ask for if I had the chance?

—Fernando Pessoa

One year ago, when we first thought about creating a website devoted to reading and literature, we turned to the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa for guidance. We needed a name, and Pessoa is a master of memorable phrases. It didn’t take long for us to remember one of our favorites: “I read the way one might stroll,” he wrote. “And it is in the classics that … I feel myself to be a sacred trespasser...”

Over the past week, we’ve been enjoying our morning coffee at the poet’s hangout, Café a Brasileira, and reading his work while we enjoy Lisbon, where he was born in 1888 and died in 1935. We also made a sojourn to Casa Fernando Pessoa, where he lived for the final fifteen years of his life.

“My country is the Portuguese language,” Pessoa wrote. Although he published only one book in Portuguese (Message) during his lifetime, critics credit Pessoa with bringing Modernism to Portuguese Literature. “Modern art is the art of the dream,” he wrote.

At age five, following the death of his father and remarriage of his mother, Pessoa moved to Durban, South Africa, where his stepfather served as the Portuguese consul. In Durban, Pessoa started signing his poetry with pseudonyms, among them Chevalier de Pas, Alexander Search and Horace James Faber. These pen names reached a new level of complexity when Pessoa started writing under “heteronyms,” each with his own biography—even family trees and astrological charts, in some cases—temperament and signature. Pessoa’s translator Richard Zenith cites at least seventy-two heteronyms. As Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet (a “factless biography” written under the heteronym Bernardo Soares), “To live is to be other. … Give to each emotion a personality, to each state of mind a soul. … Each of us is more than one person, many people, a proliferation of our one self.”

Three of Pessoa’s heteronyms are regarded as major poets in their own right.

As Pessoa wrote of them, “I see before me, in a colorless but real space of a dream, the faces and gestures of [Alberto] Caeiro, Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos. I made out their ages and their lives … I am of course still intent on publishing pseudonymously the work of Caeiro-Reis-Campos. This is a whole literature that I have created and lived, sincere because experienced, constituting a current with a possible influence—undoubtedly beneficial—on the souls of others. … I gave them each a profound concept of life, something divine, and they were all seriously attentive to the mysterious importance of existing.”

Of these heteronyms, Pessoa wrote, “I am … less real than the others, less coherent, less personal, and extremely vulnerable to their influence.”

Pessoa is to Lisbon what Kafka is to Prague. You can’t venture far without encountering his image—a cartoon here, graffiti there, an outline of his profile on the logo of a kiosk café—throughout this sun-drenched city.

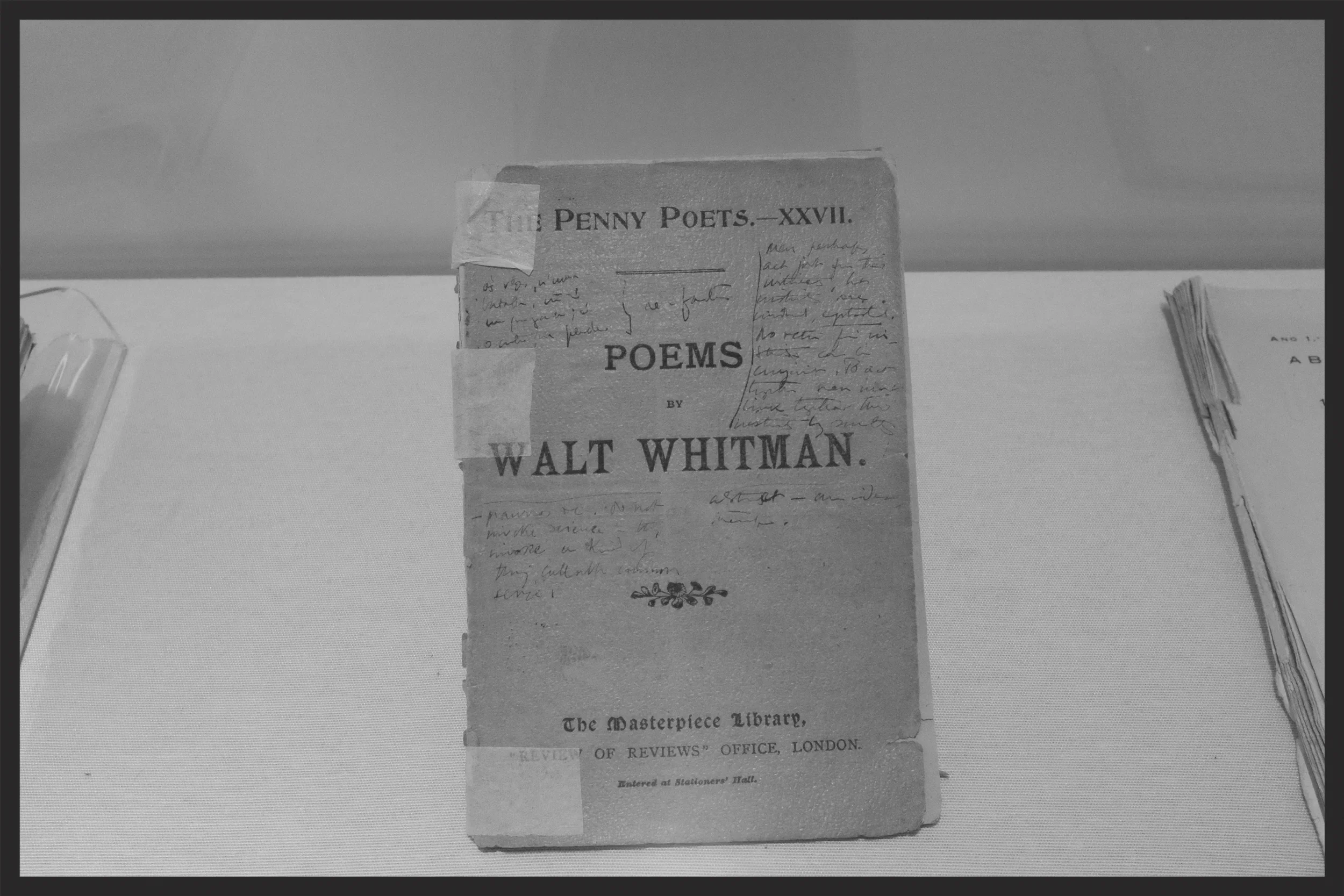

Pessoa’s copy of Poems by Walt Whitman. While Reis was a classicist and Caeiro (“the master,” in Pessoa’s words) a pastoralist, Álvaro de Campos wrote in a “sometimes hysterical voice,” as his translators Edwin Honig and Susan M. Brown describe it. Campos’s “Salutation to Walt Whitman” reminds us of the ways that great literature never stops saying what it has to say. It also demonstrates the solace that readers feel when in the company of a master. Early in the poem, de Campos addresses Whitman: “And though I never met you, born the same year you / died, / … / I know that you knew me, that you considered and / explained me.”

Pessoa made an astrological chart for many of his heteronyms, including the “stoic” Ricardo Reis. “The whole philosophy behind the work of Ricardo Reis can be summed up as sad Epicurianism,” wrote Reis’s “brother,” Federico. “Be whole in everything,” wrote Reis. “Put all you are / Into the smallest things you do.” Reis, a doctor who lived much of his life in Brazil, is a character in José Saramago’s novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, while Pessoa is a character in Antonio Tabucchi’s novel Requiem and short story “The Last Three Days of Ferdinand Pessoa.”

On the night March 8, 1914, the Pessoa legend has it, the poet wrote three of his greatest poems: “The Keeper of Sheep” by Caeiro, “Triumphal Ode” by de Campos and “Oblique Rain” by Fernando Pessoa. From “The Keeper of Sheep”: “To think a flower is to see it and smell it / And to eat a fruit is to taste its meaning.”

Pessoa was a regular at Café a Brasileira at 120 Rua Garrett in front of the Baixa-Chiado metro stop. “As a man of ideals,” Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet, “perhaps my greatest aspiration really does not go beyond occupying this chair at this table in this café.” It’s rare to stroll by the café and not see tourists and admirers of his work posing for photographs beside his statue outside the café.

From The Book of Disquiet:

… there is no disillusion in art because its illusory nature is clear from the start. One does not wake from art because, although we dream it, we are not asleep. There is no tribute or fine to pay for having enjoyed art. … By art I mean everything that delights us without being ours—a glimpse of a landscape, a smile bestowed on someone else, a sunset, a poem, the objective universe.

Literature, which is art married to thought and the immaculate realization of reality, seems to me the goal towards which all human effort should be directed, as long as that effort is truly human and not just a vestige of the animal in us. I believe that to say a thing is to preserve its virtue and remove any terror it may hold. Fields are greener when described than when they are merely their own green selves. If one could describe flowers in words that define them in the air of the imagination, they would have colours that would outlast anything mere cellular life could manage.