By Kevin Rabalais

Every reader shares some version of the fantasy. We play that Desert Island Game—what to pack when we’re finally allowed a holiday, a parade of days filled with nothing but the turning of pages. Titles tend to change with the passing of years. We discover new writers. We amend selections inside the box of books that always overflows despite our best logistical efforts.

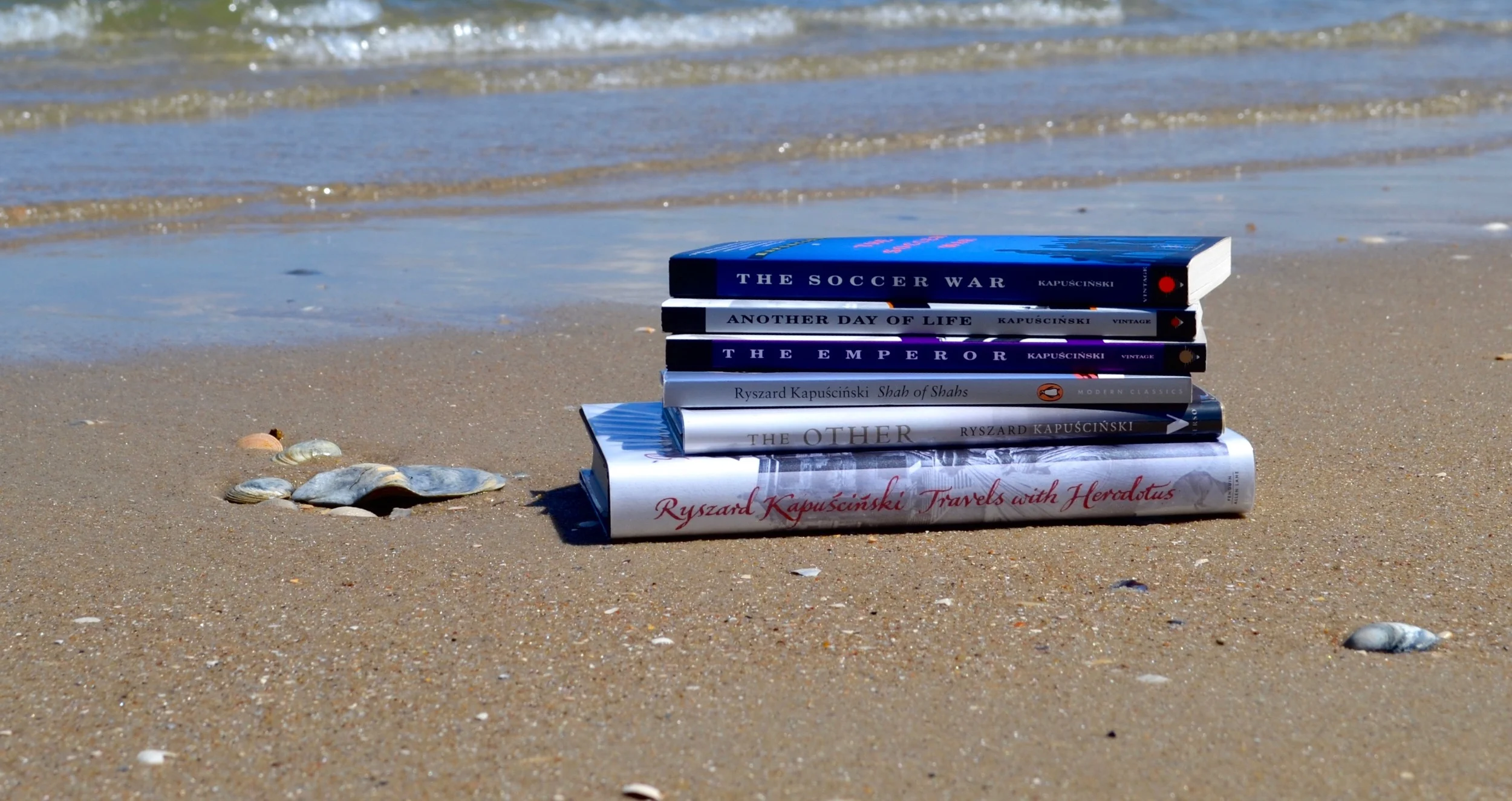

I’ve lived on three continents and have carried, to each, the work of the Polish writer Ryszard Kapuściński (1932-2007). Today, I will celebrate his birthday by rereading some of my favorite passages from his books. When it comes to my own desert island box, there’s no question that I’ll include at least one by this master of literary reportage. The headache comes in selecting which, among so many favorites.

Few months pass when I don’t reread a passage, chapter or essay from at least of one of them. Would I pack Another Day of Life, his book about remaining in Angola as one of the last journalists during the chaos the country fell into following the 1974 dismantling of Portugal’s fascist dictatorship? Or maybe it should be Shah of Shahs, about the decline and fall of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, or The Emperor, about Haile Selassie’s downfall, which Kapuściński relays through the voices of the autocrat’s associates and servants.

Then again, maybe it should be The Soccer War. This one serves as the perfect introduction—or place to revisit—this incomparable writer’s work. Kapuściński wrote these twenty-one essays—dispatches, diary entries and “Plan For a Book that Could Have Started Right Here”—between 1958 and 1980. In these pages, we follow him through Africa, Latin America and the Middle East as he rushes from one revolution and coup d’état to another.

His daily assignments were to file reports to the Polish Press Agency. But Kapuściński was always more than a mere journalist. He’s a twentieth-century master who belongs on the bookshelf among other literary game changers such as Conrad and Kafka, Fuentes and García Márquez, Kundera and Didion.

As he tells Breyten Breytenbach in Poet on the Frontline, a one-hour documentary about his life and work: “On one page of manuscript, I have to describe the whole revolution. … It doesn’t say nothing about real situation, not in a political sense, but it doesn’t say nothing about the colors, it doesn’t say nothing about smell, it doesn’t say nothing about temperature, it doesn’t say nothing about agitation of the crowd. I felt this dissatisfaction. I said, I’m the only one in this place. I have to write something more. And then I start to write my books.”

In those books, he provides the climate and atmosphere of his impressions, all that he had to leave out of the daily files. Early in Another Day of Life, for instance, he writes about the wooden crates that filled the streets of Luanda when the Portuguese started packing their belongings in preparation to flee Angola:

Everybody was busy building crates. Mountains of boards and plywood were brought in. The price of hammers and nails soared. Crates were the main topic of conversation—how to build them, what was the best thing to reinforce them with. Self-proclaimed experts, crate specialists, homegrown architects of cratery, masters of crate style, crate schools, and crate fashions appeared. Inside the Luanda of concrete and bricks a new wooden city began to rise. …

I don’t know if there had ever been an instance of a whole city sailing across the ocean, but that is exactly what happened. The city sailed out into the world, in search of its inhabitants. These were the former residents of Angola, the Portuguese, who had scattered throughout Europe and America. A part of them reached South Africa. All fled Angola in haste, escaping before the conflagration of war, convinced that in this country there would be no more life and only the cemeteries would remain. But before they left they had still managed to build the wooden city in Luanda, into which they packed everything that had been in the stone city. On the streets now there were only thousands of cars, rusting and covered with dust. The walls also remained, the roofs, the asphalt on the roads, and the iron benches along the boulevards.

Kapuściński often filed his reports under horrific circumstances and faced death on several occasions. His unflinching response throughout makes his work read like parables from a man who enters the flames because he believes he must. As he writes in “The Burning Roadblocks,” an essay about the civil war in Nigeria collected in The Soccer War: “I was driving down a road where they say no white man can come back alive. I was driving to see if a white man could, because I had to see everything for myself.”

While he tries to negotiate his passage at the roadblock of the title, guards douse him in benzene.

This unflinching urgency to locate the center of conflicts and those who create them and are forced to live in their midst spawns a cool philosophical outlook. After all, here is someone who has witnessed and undergone things that no would should have to endure. From The Soccer War:

People who write history devote too much attention to so-called events heard round the world, while neglecting the periods of silence. This neglect reveals the absence of that infallible intuition that every mother has when her child falls suddenly silent in its room. A mother knows that this silence signifies something bad. That the silence is hiding something. She runs to intervene because she can feel evil hanging in the air. Silence fulfills the same role in history and in politics. Silence is a signal of unhappiness and, often, of crime. It is the same sort of political instrument as the clatter of weapons or a speech at a rally. Silence is necessary to tyrants and occupiers, who take pains to have their actions accompanied by quiet. Look at how colonialism has always fostered silence; at how discreetly the Holy Inquisition functioned; at the way Leonidas Trujillo avoided publicity.

Among all the great passages in Kapuściński’s work, I return most often to “Dispatches,” the final essay in The Soccer War. Here, he tries to give several Ghanese an impression of Poland, a land of snow whose people never colonized any of Ghana’s neighbors. For several pages, he attempts a description.

“Suddenly I felt shame,” he writes, “a sense of having missed the mark. It was not my country I had described. Snow and the lack of colonies—that’s accurate enough, but it is not what we know or what we carry around within ourselves: something of our pride, of our life, nothing of what we breathe.”

Later, he continues:

We always carry it to foreign countries, all over the world, our pride and our powerlessness. We know its configuration, but there is no way to make it accessible to others. It will never be right. Something, the most important thing, the most significant thing, something remains unsaid.

Throughout his life, Kapuściński endured the unspeakable. His work continues to allow us the privilege to feel, as readers, what we in our otherwise limited lives might never know. And we shouldn’t have to know it first-hand, but we read this work and gain a better understanding of the world we inhabit.