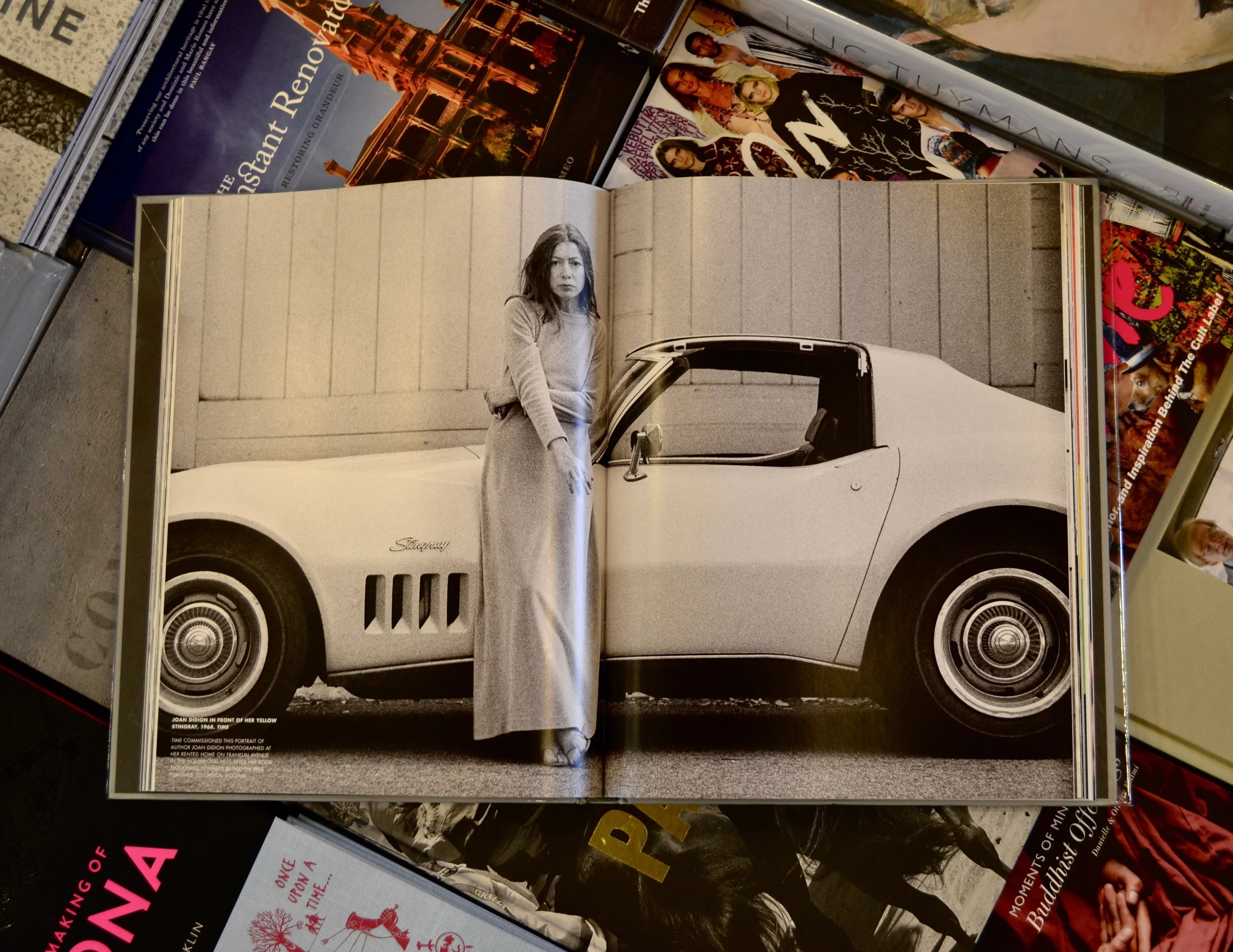

Image from Julian Wasser's The Way We Were

By Kevin Rabalais

The literary centerfold to end all centerfolds ran in 1968 after Time magazine sent Julian Wasser to photograph Joan Didion for its pages. The iconic shot belongs on every dorm room wall. Some might consider the car—Didion’s yellow Stingray—an important part of the composition. Maybe. I forget it’s there most of the time. Then there’s the cigarette, the long dress, a slight hunch, sandals crossed at the ankles. It’s the kind of pose that says, I’d rather be behind my typewriter.

But this isn’t about the pose. And it’s not about how Wasser captured Didion as what she was in that year of cultural and historical explosions: one of the sharpest, most perceptive—and, yes, coolest—writers at work.

This is about the stare.

Didion has the kind of gaze that says it knows everything about you even before you get halfway across the room. It’s a stare that threatens to punch back. If you’ve read a few paragraphs of her work, then you’ve felt the punch. We feel it in those searing sentences that make Slouching Towards Bethlehem (whose 1968 publication and critical success generated the Time coverage), The White Album, Salvador and Miami—not to mention the novels-as-detonations known as Play It as It Lays, A Book of Common Prayer and Democracy—essential reading for anyone who wants to live for a while in the presence of a writer who can knock you out the first time with her ideas and then send you down again with yet another one of her cutting turns of phrase.

I tell myself (sometimes, not always) that she probably doesn’t wear that dress from the Wasser photograph anymore. The sandals are long gone, the cigarette one of forgotten thousands. And now, Ms. Didion, we know that you’re frail. But it’s time to get serious. It’s time to know whether Joan Didion has booked her ticket to cover the upcoming Democratic and Republican Conventions. If you don’t think this is just as urgent as trying to figure out why, after all this time, we’re still laughing at Donald Trump instead of forcing him out of the conversation, please stop what you’re doing and read her political essays in the 1992 collection After Henry. Then let’s talk about how to start a crowd-funding campaign to get Didion to Philadelphia and Cleveland in July.

From “Insider Baseball,” originally published in The New York Review of Books:

It occurred to me during the summer of 1988, in California and Atlanta and New Orleans, in the course of watching first the California primary and then the Democratic and Republican national conventions, that it had not been by accident that the people with whom I had preferred to spend time in high school had, on the whole, hung out in gas stations. They had not run for student body office. They had not gone to Yale or Swarthmore or DePauw, nor had they even applied. They had gotten drafted, gone through basic at Fort Ord. They had knocked up girls, and married them, and had begun what they called the first night of the rest of their lives with a midnight drive to Carson City and a five-dollar ceremony performed by a justice still in his pajamas. They got jobs at the places that had laid off their uncles. … They were never destined to be, in other words, communicants in what we have come to call, when we want to indicate the traditional ways in which power is exchanged and the status quo maintained in the United States, “the process.”

Didion has no trouble seeing the strings behind the curtains of this mega production we call a presidential election. Maybe it has to do with her time writing scripts for Hollywood. Or maybe it’s just that she’s one of the most perceptive essayists we’ve had the pleasure of reading in the past half century. What we need, what I’m begging for here, is for Didion to do what she did in 1988. We need her observations and—let’s say it now—the enormous engine of her prose style to tell us how it is, to get inside “the process” of politics and the characters at the center of this “self-created and self-referring class, a new kind of managerial elite [who] tend to speak of the world not necessarily as it is but as they want people out there to believe it is.”

The problem, of course, is that so many among us have fallen for the characters in the process like we fall for those characters in other mega blockbusters that offer so little sustenance that we wake up the morning after a trip to the cinema unable to remember what we’ve seen. One problem is that even some of those people Didion might have hung out with in gas stations have bought into it, this storyline of politics as cheap and easy entertainment, an epic carnival that travels back and forth across the country for much too long before every presidential election.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Didion writes at the beginning of the wondrous title essay in The White Album. But is this the greatest story that we can tell ourselves at this time? A story that stars a billionaire former reality TV star whose ego seems to have been created by Melville, Twain, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Parker, Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy on a drunken night?

“All stories, of course, depend for their popular interest upon the invention of personality, or ‘character,’ but in the political narrative, designed as it is to maintain the illusion of ‘consensus’ by obscuring rather than addressing actual issues, this invention served a further purpose,” Didion writes of the 1988 conventions. She quotes one of Michael Dukakis’s political advisers, who told the Wall Street Journal that “it’s a choice between two persons.” She follows with a quote from George H. Bush: “What it all comes down to, after all the shouting and the cheers, is the man at the desk.”

In other words, what it was “about,” what it came “down to,” what was wrong or right with America, was not a historical shift largely unaffected by the actions of individual citizens but “character,” and if “character” could be seen to count, then every citizen—since everyone was a judge of character, an expert in the filed of personality—could be seen to count. This notion, that the citizen’s choice among determinedly centrist candidates makes a “difference,” is in fact the narrative’s most central element, and also its most fictive.

I could go on. There’s always more to say when it comes to Didion. But I’d be doing all of us a favor if I stop here and give you more time to go back and read those essays in After Henry and to form your own narrative about the state of the politics evolving around us as we laugh.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us via Facebook or Twitter.