By Kevin Rabalais

We all know about the maillot jaune, that yellow jersey you get to wear on the podium in Paris when you win the Tour de France, but who out there remembers the name of any winner of the lanterne rouge, the award presented annually to the slowest rider to finish the race? Readers, too, work at drastically different paces. Some burn through books. Maybe they skip paragraphs or read hopped up on caffeine, bug-eyed awake in the small hours while the baby sleeps.

Once, my own slow progress embarrassed me. But decades of reading have revealed me for what I am. So here goes. I give myself a title: World’s Slowest Reader.

For years, I told myself that the reason for my stonecutter’s pace when it comes to turning the pages has to do with being from the deep Deep South. Or maybe it’s because I hover over sentences and paragraphs, pencil in hand. Then a few years ago, a lunchtime conversation with a Booker Prize-winning novelist changed everything. Elbows on table, careful to avoid the mess of his shrimp po’boy, he reminded me that literature is not a race.

There are, however, books that carry you away like a ferocious undertow. I may never be able to read War and Peace in three sittings, but I’ll always remember how easy it was to push aside the argumentative writing essays I should have been grading the semester I read, in what seemed like one greedy gulp, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.

With some writers, it’s love at first sentence. We open their work and recognize it at once: the prose holds a charge that seems meant for us alone.

Capote arrived on the scene fully formed at age twenty-three with his debut novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), the first of his bestselling books. Read it today and you will find yourself nodding at the young novelist’s insight and lucid, stylish prose. A decade later came Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958). Then, still on the ripe side of forty, Capote set off the biggest explosion of his career—and one of the greatest in post-war American literature—with In Cold Blood (1965).

There’s an old saying that if you were born after Elvis’s death, in 1977, you can only remember the King as that flabby guy in a white jumpsuit. So, too, did Capote’s radiance fade after the publication of In Cold Blood. He promised a novel in which he would outdo Proust but failed to deliver with the highly anticipated (and posthumously published) Answered Prayers. In his later years, Capote resembled a celebrity cursed with so many addictions that he lost the drive and ethic that made him one of the purest writers of American prose the twentieth century produced.

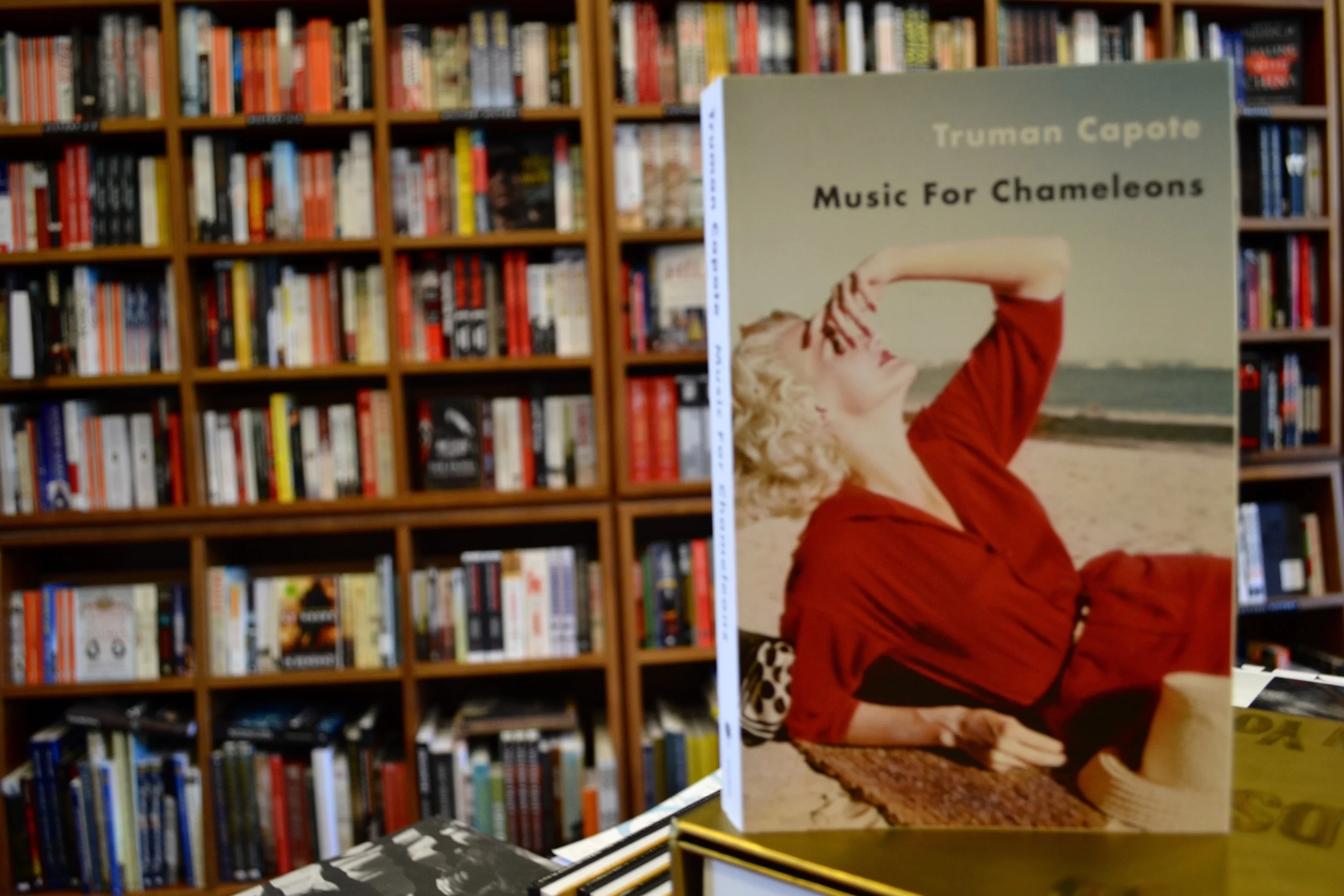

In 1980, when the promise of Answered Prayers still seemed possible, Capote published one of his greatest books, and the last he would see in print during his lifetime. The literary reportage in Music for Chameleons contains some of Capote’s best writing. And while readers know In Cold Blood like cycling fans can rattle off winners of the yellow jersey, it makes no sense to me why we don’t talk about “Handcarved Coffins”—the “nonfiction short novel” and centerpiece of Music for Chameleons—with the same fervor we use to praise In Cold Blood.

A capsule description of the plot, with a caveat: we read Capote not for what happens but for how he reveals it. Subtitled a “Nonfiction Account of an American Crime,” “Handcarved Coffins” begins in March 1975, in “a town in a small Western state.” Capote, whose persona remains absent from the pages of In Cold Blood, places himself in the middle of the action of an ongoing investigation, a series of strange crimes in which the victim, or victims, receives in the mail a small coffin carved from balsa wood. Each coffin contains a photograph, a clue about how the victim will die.

Many of the “facts” of the investigation and crimes that Capote describes have since been discredited, but reading Capote is more about surrendering ourselves to the influence of a writer who welcomes us at the gate of his work and treats us like treasured guests as he guides us through the rooms of his stories. To put it simply: Capote seduces us with his style. “To begin with, I think most writers, even the best, overwrite,” he writes in the preface to Music for Chameleons. “I prefer to underwrite. Simple, clear as a country creek.”

As his career advanced, Capote moved further and further from the pure fiction that made him famous and into “journalism as an art form.” He cites two reasons for this:

First, it didn’t seem to me that anything truly innovative had occurred in prose writing, or in writing generally, since the 1920s; second, journalism as art was almost virgin terrain, for the simple reason that very few literary artists ever wrote narrative journalism, and when they did, it took the form of travel essays or autobiography.

One collection of such journalism, The Muses are Heard, appeared in 1956. That book, Capote writes in the preface to Music for Chameleons, “set me to thinking on different lines altogether: I wanted to produce a journalistic novel, something on a large scale that would have the credibility of fact, the immediacy of film, the depth of freedom of prose, and the precision of poetry.”

For the rest of his productive life, he worked toward that goal, honing that “simple, clear as a country creek” style, and ultimately giving us In Cold Blood and “Handcarved Coffins.” The latter deserves a second look. And then a third. Read it fast, breathless. Then go back, pencil in hand, ready to be astonished all over again in slow motion. While you read it, savor that prose and challenge me for the title of World’s Slowest Reader. Even if you lose, you’ll have rewarded yourself with a few of the most memorable hours you will ever spend with a book.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us via Facebook or Twitter.