Walker Percy, The Moviegoer and the Many Ways the 1962 National Book Award Winner Still Provokes and Encourages Us More Than Fifty Years After its Publication

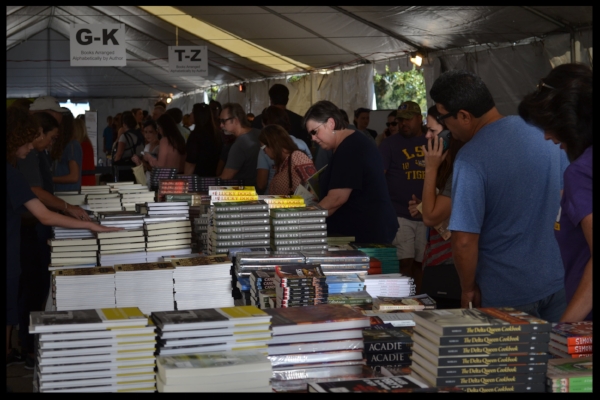

A Book Talk by Jennifer Levasseur, editor of Walker Percy's The Moviegoer at Fifty, Louisiana State University Press

(Given at the Louisiana Book Festival, the State Capitol in Baton Rouge, October 29, 2016)

Let's begin with a musical introduction to set the mood: "Yes We Can Can" by the late, great Allen Toussaint.

I don’t know much about Walker Percy’s musical tastes. I don’t know how he felt about Allen Toussaint or this song that the great lyricist and musician wrote in 1970, but I’ve connected them somehow in my own personal mythology of New Orleans experience: this infectious, optimistic ballad that encourages us to be good to each other (and, surely, to dance) and Walker Percy’s first novel, published almost a decade earlier, in 1961, that continues to set us on—or reminded us of—the search. Walker Percy defines the search as “what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. … To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.”

We are all looking for that extra beat to life, as Richard Ford has called it, something akin to what Percy referred to as rotation. That something extra that takes us beyond waking every day and going to work and following the rules and leaning one step closer toward death. That spark that sets our blood to boil or leaves us giddy with an excitement we don’t yet understand, that pushes us out of and into ourselves simultaneously.

“Yes We Can Can” doesn’t tell us that we’re bad or that we’ve caused any of the many problems our community faces (that’s for some other time), but it fires us up to do better, to be better and to help others be and do better. The Moviegoer—so much more wry and knowing than Toussaint’s catchy tune—does something of the same. It acknowledges a problem and a desire for more. Even though we’re each responsible for our own lives and must captain our own searches, we need each other to forge that course, to help direct us when we go astray, to push us off that course sometimes, to welcome us back, to force us to rethink our directions (and our destinations) and to call us out when we’re spouting nonsense. Binx, narrator of The Moviegoer does this, at least internally, when his cousin Nell exclaims her defiance of gloom, her cheerfulness in the face of every difficulty. He’s so embarrassed for her that he can’t meet her eyes, and his bowels rumble, his body threatening to explode even as civility forces him to swallow his disagreement.

My Walker Percy—and we fans each have one, which I think (and hope) he wouldn’t mind—appreciates “Yes We Can Can,” as long as it sits alongside a good helping of realism and existential doubt. This helps me understand Percy’s Catholicism—his bad Catholicism, as he would explain it: the trying to do good, the failing, the seeking of forgiveness and making amends, the attempt to do better, then failing again. Binx Bolling, on the other hand, might find the song a bit too easy, and it might hit a little too close to home for him. While he understands the need for the search—again, “what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life”—he admits that he prefers the imagery and escape of films over the reality of his experience.

Before I talk too much about The Moviegoer and Binx and the other book I’m really here to talk about, Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer at Fifty, I’d like to make a confession.

I’m here today giving my best impression of a Walker Percy expert. As his biographer the esteemed Jay Tolson writes in the funny and confessional foreword of this book, I don’t want to be a vampire, sucking the lifeblood of one of the best writers the South has ever produced. I don’t want to feast on his work or try to build myself up by scaling his legacy. As Tolson explains, “becoming a Percy specialist began to give me a metaphorical case of the hives.”

So I am not a Percy expert, and there are far more learned scholars than I who can explain his semiotic studies, his exploration of existential philosophy, his reliance on the writing of Saint Augustine, and the legacy of his work—you may be in the audience now and I encourage you to read many of them here in this loving tribute to his most influential novel—but what I am is a fan. One of those embarrassingly devoted fans who name their dogs after him (my apologies to Walker Percy’s daughters). One who rereads The Moviegoer again every few years because it’s new every time and it makes me want to upend my life every time, and it makes me laugh and it makes me cry and it helps me to understand even more this city and this state that I love in all its glaring faults.

I am a daughter of Plaquemines Parish: Louisiana’s most southern parish, the ends of the earth, home of rich soil, of a legacy of crooked politicians (I hope I don’t get struck by lightning by saying that in a Senate room), of salt-of-the-earth people (those souls you find in the best Fonville Winans photography), and of Becnel citrus (ask me after this if you want to talk about where to get the best satsumas and navels; I’ll hook you up), but I’m often far from home, living in New Zealand or France, or, for much of the past twelve years, Australia. Like Percy and Binx, I’m on the search, though it would have been easier if I’d settled for what he calls “the little way”: “not the big search for the big happiness but the sad little happiness of drinks and kisses, a good little car and a warm deep thigh.” So while I have a PhD in literature and writing and I’ve been a bookseller for decades (including at Maple Street Book Shop, where Walker Percy reigned as its patron saint and where we stocked a full bookcase of volumes by and about him), I am not a specialist in Southern or even American literature.

But Walker Percy and The Moviegoer have been a part of the journey of my entire adult life. By the time my teenaged self traveled Uptown to Dominican for high school, he had already found his final resting place on the grounds of Saint Joseph Abbey, so I never looked into those kind, soulful eyes or touched his hand. And yet we know each other all the same. I find myself—and lose something of myself that needs to be sloughed off—every time I read one of his books. He teaches me and he comforts me. He writes about me. And he’s created another family for me, because there are so many of us out there, fans who read these books over and over because Walker Percy’s characters and his ideas just keep talking. Even as he discusses the existential despair, the isolation of living, he pulls us all together. Even if we’re alone, we’re alongside many others who are trying—and sometimes failing—right here next to us.

Each of the fourteen essayists in this collection is a Walker Percy fan, a devoted one. Each one has read and reread and poured over The Moviegoer because this novel has sparked something in them that left them unable to sit still or to put the book aside to move on to the next thing. Walker Percy scholars, as a group, are some of the best people I’ve ever come across: they’re generous, they listen, they question, they support one another, and they share information. I haven’t met one who’s proprietary. They know what a gift Walker Percy’s works are, and they know how much richer the experience can be when we slow down and consider the words on the page and what’s behind them, why he structured the novel the way he did, how it can speak to us, what it’s calling us to do. And even when those readings of his work conflict or lead to opposing conclusions or reconfigure what we thought we’d understood—and these essays do just that—Walker Percy fans know that this is simply a function of the generosity of The Moviegoer, of its nuance and of its ability to be what we need it to be at any given moment. These are some of the many reasons that more than fifty years after The Moviegoer’s publication, it remains an influential, iconic work that serves as a precursor to so much good writing in the United States and particularly in the South.

Because of this, it’s important to remember the many obstacles that stood between Walker Percy and the publication of The Moviegoer. What now seems like an obviously enduring classic, one that our grandchildren and their grandchildren will read, easily could have lingered in a bottom drawer of a desk or been forgotten as yet another first novel by an unknown that few bought and fewer read. Percy wrote two never-published novels before The Moviegoer. Even once he’d completed Binx’s story of living in Gentilly—romancing the secretaries in his brokerage firm, watching movies, avoiding Mardi Gras and knowing that there has to be more than scratching off the days—the road to publication nearly ended several times. A less driven writer would have given up in despair or squirreled his precious treasure away, unwilling to attempt the major revisions the editor recommended.

But Walker Percy was no stranger to challenges. During his medical residency, he contracted tuberculosis and spent years in sanatoriums and at mandatory rest. He used the time to explore philosophy and read the classics. Much later, he and his wife discovered that one of their daughters was deaf and they set out to create a curriculum so that she could learn and communicate effectively. So when an editor at Knopf liked The Moviegoer but said it needed work, Percy went back to it. And when the editor liked the second draft but thought it needed even more work, Percy worked on it again. Through every one of these critiques, Percy (surely, gritting his teeth and with a few curses) went back to work. Finally, when they arrived at an acceptable manuscript, the editor lost his job, and Percy lost his champion. The novel sold few copies even though early critics lauded its merits, including a glowing review in the New York Times that ran on Percy’s forty-fifth birthday.

“Literary success is a fluke. But quality isn’t.”

Through an unorthodox course of events too convoluted to discuss here but magically fortuitous, The Moviegoer found itself on the shortlist for the 1962 National Book Award, alongside J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, The Chateau by William Maxwell and Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, quite an illustrious party to be invited to. To everyone’s surprise, The Moviegoer, a first novel by a completely unknown writer about a war veteran obsessed with movies and at times buried in existential angst, won. Even his publisher was shocked—and disappointed. Alfred A. Knopf had personally backed The Chateau. Who was this upstart?

After the win, this slim novel set in the lead-up to Mardi Gras—but avoiding it almost entirely, giving no one the tourist’s view of local color and refusing to explain its idiosyncratic New Orleans-ness—this slim novel about a young man on the brink of a quiet, even controlled, crisis became as much of a household name as any literary novel can be. Percy appeared on TV, people raged about and loved the novel, and as time passed, students and aspiring writers made pilgrimages to see the great man.

Literary success is a fluke. But quality isn’t. Even if The Moviegoer had remained a quiet book with only a few dedicated, adoring readers, it would still be a landmark work. We’re lucky that it now appears on nearly every list of great New Orleans and great Southern novels, and it should appear on more tallies of great American literature.

As we talk about it here today, The Moviegoer is in what we’d call middle age or even older, if we’re thinking in human years. We’ve had the pleasure of these pages for more than fifty years, but they feel as relevant now, as fresh, as irreverent and as provocative as they must have seemed in 1961. That’s one of the many reasons we can’t stop talking about The Moviegoer and why so many readers and fans can still, all these decades later, unearth new treasures embedded in Binx’s story of loss and love and death and human frailty.

The Moviegoer at Fifty, like the novel it discusses, is full of wonder, of wry humor, of challenging ideas, of theology and movies, and of surprising yet utterly fitting diversions. I think Binx would approve.

“Me, it is my fortune and misfortune to know how the spirit-presence of a strange place can enrich a man or rob a man but never leave him alone, how, if a man travels lightly to a hundred strange cities and cares nothing for the risk he takes, he may find himself No one and Nowhere.”

The collection is made up of three parts by writers from around the United States and from Spain who answered the call to reflect on the five-decade life of The Moviegoer, a novel that long has had a huge canon of academic study and is also widely discussed in the commercial and popular media. These writers looked for new ways to read the novel, alternate views, and ideas and questions that might have been touched on but hadn’t been previously explored in-depth.

Jay Tolson wrote the foreword in Prague while musing on reading The Moviegoer for the first time on a Kindle and while looking out over Kafka’s grave, and I edited the collection while bouncing between—or as Binx might say it, spinning along—New Orleans and Australia. This, as anyone who knows The Moviegoer understands, would make Binx very uncomfortable. He’s clear that new, foreign places upset the little way, make you question your choices and who you are in the world, for better and for worse. Even a brief business trip to Chicago from New Orleans is abnormal enough to wobble his compass. He tells us:

Me, it is my fortune and misfortune to know how the spirit-presence of a strange place can enrich a man or rob a man but never leave him alone, how, if a man travels lightly to a hundred strange cities and cares nothing for the risk he takes, he may find himself No one and Nowhere. … What will it mean to go mosying down Michigan Avenue in the neighborhood of five million strangers, each shooting out his own personal ray? How can I deal with five million personal rays?

The essayists in The Moviegoer at Fifty have traveled from their homes around the country and around the world to make pilgrimages to New Orleans and Covington and Chapel Hill, where the bulk of Percy’s papers are housed, threatening their own surety in order to understand Binx and Percy’s others characters that much better. They are specialists in a variety of fields: theology and religion, literature, philosophy, disability studies, film and media, music. They are seekers, bouncing between the little way and the grand search.

In these pages, we learn more about Walker Percy’s influences, from Saint Augustine to Cervantes, Dostoevsky and Heidegger. We discuss the role of film in the novel and how The Moviegoer can speak to new technologies that Binx couldn’t have dreamed of, including Twitter and Facebook. Worthy of its own chapbook, a comprehensive and amusing dictionary-style cheat sheet to all of the movie references in The Moviegoer demystifies and contextualizes the films influencing Binx and coloring his experiences. For those who are counting, that’s twelve named films, a few mysterious unnamed and possibly fictional ones and forty-five actors. The essayists, Jonathan Potter and Read Mercer Schuchardt, also include contemporary analogues of these actors for those too young to fully grasp the significance of Binx’s references.

The collection concludes with several artists in Walker Percy’s bloodline, those who have used in some way The Moviegoer as a model for the search, from the wonderful short story writer and novelist Tim Gautreaux to The Boss (Bruce Springsteen).

In the collection’s foreword, Jay Tolson welcomes us inside the biographer’s psyche and his fears in writing a person in the round. He describes years of Walker Percy dissuading him from his task, of their standoff, of Percy’s desire not to talk about what he called his “decrepit character.” If anyone here is considering writing a biography of a living person, I encourage you to read Tolson’s account of a dream he experienced late in writing Pilgrim in the Ruins:

In my dream, Walker and I were not playing [golf] but simply walking through a thick early morning mist when he suddenly collapsed. I lifted him up and carried him fireman-style to a small local hospital. We waited for a while until a physician, an African-American, came in and intubated Walker and ordered me to blow into the tube, which I dutifully did, but apparently not hard enough. One of Walker’s eyelids lifted slightly. He looked at me with a stern gimlet eye and said, “Blow harder!” The order ran through me like an electrical shock. I woke up, pulled myself out of bed, and went right to my desk. … No wonder so many biographers end up turning on their subjects, or become depressives resisting the impulse to do so.

Literary studies sometimes get a bad rep. We sometimes see a book about a novel and think, That’s just too much hard work, like being back at school. It can seem like dissection: you take something beautiful and amazing and complete and you pull it apart until it’s a pile of stringy pieces, good for nothing and impossible to make whole again. This is not that book. The styles of these essays are wide-ranging and their levels of challenge vary, but these essayists are not destructive. They add to the novel rather than strip it clean. They are passionate, insightful, funny. They’ve taught me many other facets to my Walker Percy and my Moviegoer, in the same way that parents can discover more about their children when they meet their friends and see another part of their kid’s personality.

Like the essayists, I find something utterly new and unexpected each time I read The Moviegoer, usually a thing I can’t imagine having missed the first or fourth time I read the novel. This week, I was startled by Binx’s discussion of politics and the vitriol opposing pundits and parties and citizens can spew. Don’t get nervous, I’m not going to stay with politics too long. But I want to share this because I’ve never heard anyone handle the divide in quite this way. Here’s what Binx does:

Whenever I feel bad, I go to the library and read controversial periodicals. Though I do not know whether I am a liberal or a conservative, I am nevertheless enlivened by the hatred which one bears the other. In fact, this hatred strikes me as one of the few signs of life remaining in the world. This is another thing about the world which is upsidedown: all the friendly and likeable people seem dead to me; only the haters seem alive.

Now, don’t get too saddened by this. What I love about Binx—and remember, he’s at a crossroads, dealing with the aftershocks of PTSD, questioning everything he’d previously decided about how to live, knowing his kid brother is dying and worried about his cousin on the brink of a breakdown, all while remaining utterly calm—is that he’s honest about what he’s feeling even if he knows his feelings aren’t what they should be. And I love that no matter his political preference, if he even has one, he sits quietly in a place of learning to read the most extreme views from each side, one at a time, truly engaging with their arguments, lauding the writers when they make an inarguable point. He doesn’t force himself to draw easy, or even difficult, conclusions. For now, he listens and he ponders. And, yes it’s true, he feeds off the passion he witnesses.

Which is what we all do. We readers look to books, particularly to special books like The Moviegoer—at least in part to supply that extra beat to life, to move us outside the everyday, to give us endless second lives and alternate possibilities. To give us the rotations and revolutions Binx talks about. To set us each on the search, or to encourage us through it, and to help us discover when it’s time to accept the comfort and ease of the little way.