By Kevin Rabalais

In 1956, a seven-year-old Bruce Springsteen watched Elvis shake it on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“When it was over that night, those few minutes, when the man with the guitar vanished in a shroud of screams, I sat there transfixed in front of the television set, my mind on fire,” he writes in Born to Run, a memoir that deserves its place on the shortlists of upcoming major literary awards. “I had the same two arms, two legs, two eyes. I looked hideous but I’d figure that part out...”

The look—what Springsteen saw and admired in Elvis: “his eyes, his face, the face of a Saturday night Dionysus”—he began to hone in front of his childhood mirror. By his early twenties—a few years before he appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek and critics and fans greeted him as the future of rock and roll—he would clock more than a thousand nights on East Coast barroom stages.

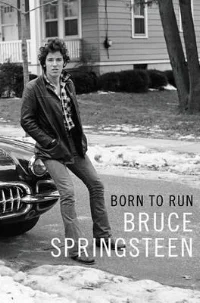

It would have taken the greatest casting agent in Hollywood history to discover a better persona for the gig. Here he is, slouched and grinning in that iconic Eric Meola photograph on the cover of Born to Run (1975). First, the image. In that twenty-four year old on the Born to Run cover—torn T-Shirt, messy hair, trusted Telecaster in hand and wearing a leather jacket that has worked coast to coast and back again—we find a kind of Billy the Kid meets Rimbaud cum the kind of guy you’d want to call a best friend and take home to meet your sister. Then the music starts. And with Springsteen, that music always feels like a necessity. Out of the piano and harmonica that spark “Thunder Road” rise the first lyrics, and at once you understand that something more is at stake here than a rock and roll album.

Born to Run seeks to at once to define and exhaust a genre. Springsteen never, including in this memoir that takes its name from his most famous album, gives less than everything. With his debut as an author, he makes a contribution to American Literature.

After seeing Elvis perform that night on TV, Springsteen understood what had been missing from his life—“the ‘ANSWER’ to my alienation and sorrow, [the guitar] was a reason to live,” he writes, “to try to communicate with the other poor souls stuck in the same position I was.” While his parents couldn’t afford to buy him a guitar, his mother, a lover of Top 40 music, understood her son’s dream. Through her passion for music, the young Springsteen gleaned the words and music of The Drifters, Sam Cooke and Roy Orbison—all those records that “summoned the joy and heartbreak of everyday life,” as his own songs would later summon for millions around the world. She took him to a local music store and rented a guitar. At home, little Bruce stood in front of the mirror and worked his moves. Soon he grew frustrated with the complex new instrument, which they returned.

Years passed. He got a job. He bought a guitar. Then he learned how to make it talk.

Born to Run reveals a shy and introspective Springsteen, a Jersey-born Catholic boy with the soul of a poet and a dream to make music that not only sends people into fits of elation but forces them at once inward and to larger thoughts outside of themselves. He chronicles his unceasing desire to make music and understand his time, place and the people he lives among. Springsteen’s lyrics, so easily misunderstood or forgotten beneath layers of an often-nuclear sound (even Ronald Reagan would have understood “Born in the U.S.A.” in the version Springsteen originally intended it to be heard), examine the personal and political, the individual struggling for a place within society, in the workplace, in the family, in love.

My model was the individual traveler, the frontiersman, the man in the wilderness, the highwayman, the existential American adventurer, connected but not beholden to society: John Wayne in The Searchers, James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, Bob Dylan in Highway 61 Revisited. These would later be joined by Woody Guthrie, James M. Cain, Jim Thompson, Flannery O’Connor—individuals who worked on the edges of society to shift impressions.

On the page, Springsteen writes with a voice as distinct as the one that we hear, in memory, on an old tinny car radio, driving deep into the night on an empty highway, with nothing but the energy and wisdom of Darkness on the Edge of Town or The River or Nebraska or The Rising to light the way. The voice may not be beautiful, it offers little range, he acknowledges, but it works with an enviable hunger and ethic. And the ethics of his memoir reveal something much more than a songwriter and guitar man. Here we witness the emotional and working life of a writer whose great search places him firmly inside the American tradition of Henry David Thoreau, who went to the woods because he “wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” He went to rock and roll for much the same reason that Thoreau went to the woods.

I fought my whole life, studied, played, worked, because I wanted to hear and know the whole story, my story, our story, and understand as much of it as I could. I wanted to understand in order to free myself of its most damaging influences, its malevolent forces, to celebrate and honor its beauty, its power, and to be able to tell it well to my friends, my family and to you. I don’t know if I’ve done that, and the devil is always just a day away, but I know this was my young promise to myself, to you. This, I pursued as my service.

We hear it in the knowledge, engagement and questioning of “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” “The River” and “American Skin.” We feel it in the overwhelming energy of “Backstreets,” “Crush on You” and those unforgettable live performances—“Light of Day,” say, one of dozens of Springsteen songs that any band would be happy to promote as their greatest hit and yet easily is forgotten in the breadth of his canon, the kind of music that encourages you to get up and work it much like that little boy did all those years ago.