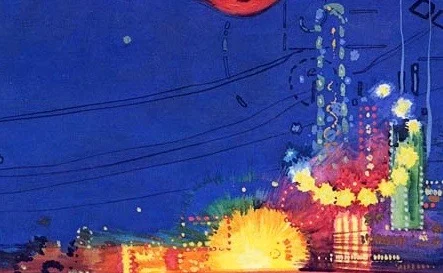

Photo: Detail from Francis Cugat's cover design for the first edition of The Great Gatsby

By Mark Sarvas

It is the first Sunday in January, sunny and warm in my Santa Monica apartment, as I write these words. What that means is, once I’ve hit the send button on this essay, I will retreat to the comfort of my favorite chair and commence one of my essential annual rituals—I will read The Great Gatsby in its entirety in a single sitting. It has been my first book of the year since 1993, though my history with my favorite novel goes back to 1984.

By some astonishing quirk, I’d finished my primary and secondary education without ever having been made to read the novel. A close college friend expressed his considerable surprise at this gap in my reading, and promptly bought me a copy, telling me that I reminded him of the titular hero. At the time, I took that to be a compliment—those heady college days were, for me, a time of constant romantic tumult and I liked the comparison. As my twenties would give way to my thirties and forties, as Gatsby’s tragic, doomed nature became clearer to me, I was less convinced the remark had been intended as praise. Now, at the beginning of my fifties, I’ve made a kind of friendly peace with the partial truth of his sentiment.

But in that initial read, I was young and shallow and couldn’t yet appreciate descriptions like this one of Tom Buchanan: “ …one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anti-climax.” I was, after all, still ten years younger than the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, who memorably turns thirty in the climactic seventh chapter of this short novel: “Thirty—the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair.”

But what even I couldn’t miss was the language. Fitzgerald’s luminous prose that left an immediate and lasting mark on me. It was in a sentence-drunk imitative fit that I wrote my first short story within days of finishing the novel. And thirty years later, when I decided to get my first tattoos as I approached fifty, I turned, inevitably, to Gatsby. The opening words of the novel are now found on my right arm; the unforgettable closing, “…borne back ceaselessly into the past” on my left. In between those moments, Gatsby has been an inextricable part of my own journey as a novelist.

When I was invited by the Melbourne Writers Festival to teach my first course in novel writing, I returned to Gatsby and built the entire lesson plan around the novel. Gatsby followed me to my novel writing classes in UCLA, where I explained to my students that while many teachers like to use samples from many works, Gatsby is one of the few novels I know that does everything nearly perfectly—structure, plot, theme, character, language. Gatsby is one of those rare, divine moments every writer dreams of. (Fitzgerald himself seemed to know as much when he described the book to his legendary editor Max Perkins as a “consciously artistic achievement.”)

After more than thirty years of reading Gatsby, my shelf contains Hungarian and French editions. (I speak the former and use the latter to help me brush up on my tattered French.) I have a wonderful boxed facsimile first edition, featuring Francis Cugat’s iconic cover (the same image that adorns that first paperback given to me by my college chum, which sits beside it). I have my teaching prompt copy (now tattered and falling to bits). I also have a dozen associated titles, including Trimalchio, an early draft of Gatsby; as well as editions of Fitzgerald’s remarkable correspondence with Perkins.

And still, I sit down eagerly each January to take up the novel once more. To read the book in a sitting is not quite so odd as it sounds—it’s a svelte 50,000 words. (Such brilliant economy!) The Elevator Repair Service’s recent, sensational staging of Gatz—a live, daylong performance of every word of the original text—only reinforces the compact power of the novel’s drama.

In the end, if one may be permitted the inevitable cliché, one truly does find something new with each reading. As I’ve aged, as I’ve grown as a writer, as I have begun to savor some of the anti-climax, and felt my own brief-case thin a bit, the novel has repurposed itself with every reading. In my thirties, when I worked in an office, I had a conversation with a colleague, a man in his sixties, about my annual tradition. He quite literally could not understand why I would read a book a second time. “But you know what happens already!” he insisted, astonished by my unusual behavior. I remember telling him, a bit pompously I fear, that any book worth not worth reading twice wasn’t worth reading once. I also explained that the consolations of Gatsby were not, primarily, the plot; and that as I got older, the book took on new forms for me.

Skeptical, he want back that evening and re-read a beloved book from his college days. It was a revelation, he informed me, and spent the rest of that excited summer revisiting old literary friends. He is just one of the many memories that fills my head the first Sunday of each January, as I beat on against the current.

Mark Sarvas’s second novel, Memento Park, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2017. His debut novel, Harry, Revised, was published in more than a dozen countries. His book reviews and criticism have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Threepenny Review, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Bookforum, The Dallas Morning News, The Barnes and Noble Review and The Los Angeles Review of Books (where he is a contributing editor). He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and PEN/America, PEN Center USA. He lives in Santa Monica and teaches advanced novel writing in the UCLA Writers’ Program.

To receive updates from Sacred Trespasses, please subscribe or follow us via Facebook or Twitter.