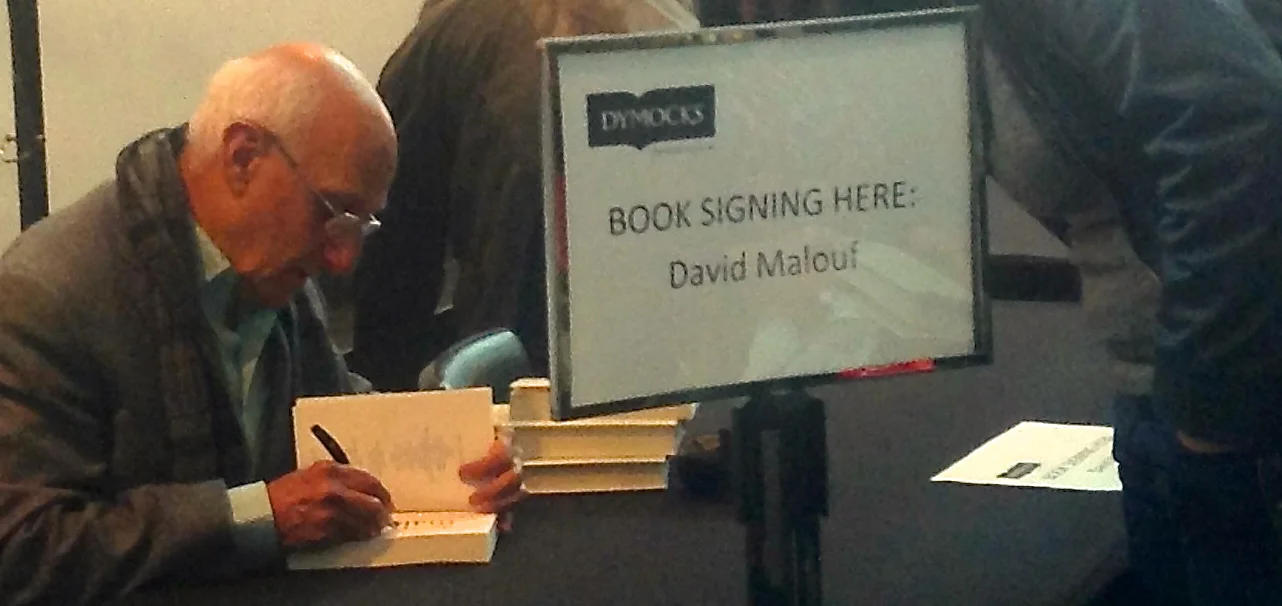

Last week, I had the honor of interviewing Neustadt Prize-recipient David Malouf on stage at the Melbourne Writers Festival. The following is a version of my introduction:

In the next few minutes, you’re going to hear me say the name David Malouf more than half a dozen times. I repeat the name David Malouf again and again only because I feel like someone who has made a discovery, forty-five years after David Malouf’s first book appeared, and who finds himself still ecstatic with his great good fortune as a reader.

To begin this morning with Goethe, that early supernova of literature, Goethe, who wrote that one should, each day, read a good poem, hear a song, see an exquisite picture and, if possible, speak a few reasonable words. A rich day, indeed, and yet we have the privilege of encountering everything that Goethe suggests in the pages of David Malouf’s nonfiction, the subject of our session this morning.

“It is difficult to get the news from poems,” as William Carlos Williams writes, “and yet men die every day for lack of what is found there.” Where Williams writes of poetry, I take him to mean something more encompassing, literature with a capital L, the kind that provides us with the news that makes sense of ourselves and others and helps us to better comprehend the world we inhabit.

Beginning last year on the occasion of his 80th birthday, David Malouf published the first of what would become, over the next twelve months, three books of essays. They are, in order, A First Place (about place and identity), The Writing Life (about literary matters), and Being There (a volume about what David Malouf calls “the culture we live in” and which also includes his libretti Voss and Mer de Glace as well as a dramatic version of Euripides’ Hippolytus.

This next part, though it may sound like a parlor game, provides reader with an education. Open any of these volumes at random. What you will find, on each and every page, is the kind of news that comes to us all too rarely—the kind of vital news that presents us with what Henry David Thoreau deemed the highest achievement that the arts can offer us. And that is, to quote Thoreau, “To enhance the quality of the day.”

I suggested that it’s fulfilling even when we open these pages at random because David Malouf has always been the most generous of writers. This isn’t someone who offers bread and water and then seats us on a dusty floor. This is a writer who brings out the full banquet and then positions us beside him at the head of the table. For that reason, we read his work with a pencil in hand so that we can underline passages. We read his work and find ourselves eager to discuss and share it with others.

Through his poetry and novels, his stories and libretti, his essays on subjects as diverse as the operas of Verdi and Wagner or the film Some Like it Hot, the art of photography, the psychological effects that landscape has upon us, the novels of Thomas Mann or the poetry of Whitman and Lawrence, David Malouf has been enhancing the quality of our days—enhancing, indeed, the quality of his readers’ lives—for five decades. The contents and breadth of these three collections reveal a writer who moves through life, always astonished. As readers, we should consider ourselves fortunate that he chooses to report his findings back to us.

That’s only one of many reasons that I find this final reference to be the greatest of honors: Ladies and gentleman, Mr. David Malouf.

To subscribe to Sacred Trespasses, please contact us with the message "subscribe."