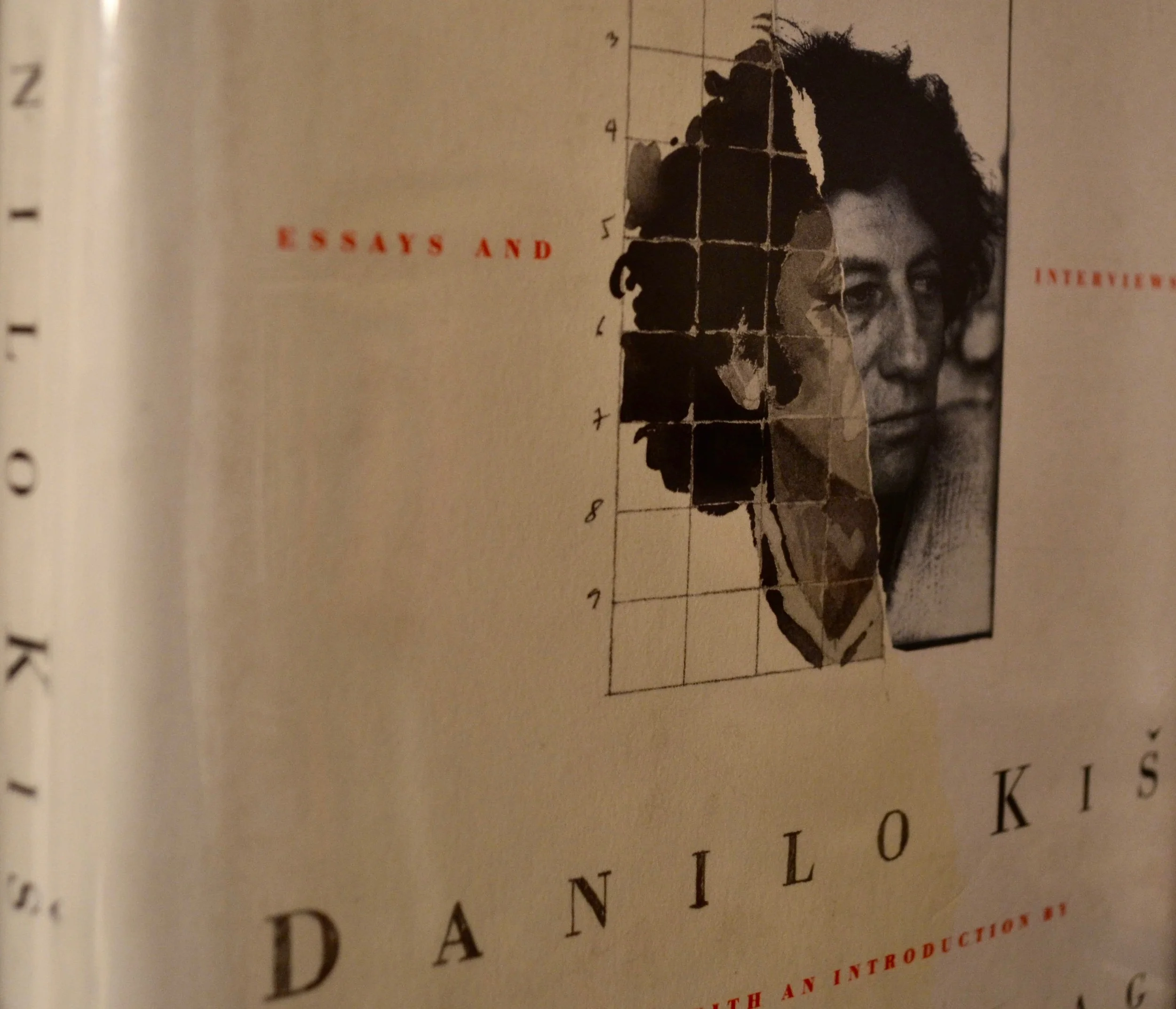

The barista in the café nearly jumps over the counter to get a closer at the book on the table: Homo Poeticus by Danilo Kiš.

“That’s the guy who wrote A Tomb for Boris Davidovich,” he says. “It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read.”

He’s twenty years old and marketing the lower shelf of a hardware store on his face. We probably wouldn’t be able to agree on the temperature outside. And yet. Literature like a shared passport provides this brief moment of shared joy between strangers. The experience, rare under any circumstance, is even more surreal given the author in question. The Subotica-born Kiš (1935-1989), once a darling of international letters, author of Garden, Ashes (a novel that Joseph Brodsky called “A veritable gem of lyrical prose, the best book produced on the Continent in the post-war period”), has been grievously neglected since his early death from cancer at age fifty-four. He would have been eighty this year.

Kiš’s father was born in Austro-Hungary, an area that now belongs to Montenegro. Eduard Kiš and several members of his family died in various Nazi concentration camps. The young Danilo later moved with his mother and sister to Yugoslavia.

This personal history, along with the fate of geography, haunt the writer’s work—slim but burning books that blend history and fiction and often read like prose poems.

We witness this in the opening to “The Knife with the Rosewood Handle,” the first of seven parts that comprise Kiš’s novel A Tomb for Boris Davidovich:

The story I am about to tell, a story born in doubt and perplexity, has only the misfortune (some call it the fortune) of being true: it was recorded by the hands of honorable people and reliable witnesses. But to be true in the way its author dreams about, it would have to be told in Romanian, Hungarian, Ukrainian, or Yiddish; or, rather, in a mixture of all these languages. Then, by the logic of chance and of murky, deep, unconscious happenings, through the consciousness of the narrator, there would flash also a Russian word or two, now a tender one like telyatina, now a hard one like kinjal. If the narrator, therefore, could reach the unattainable, terrifying moment of Babel, the humble pleadings and awful beseechings of Hanna Krzyzewska would resound in Romanian, in Polish, in Ukrainian (as if her death were only the consequence of some great and fatal misunderstanding), and then just before the death rattle and final calm her incoherence would turn into the prayer for the dead, spoken in Hebrew, the language of being and dying.

Susan Sontag, a friend of Kiš who collected and edited the essays and interviews in the posthumously published Homo Poetics, calls the writer “a poet in prose and prince of indignation.”

He had a reason for the latter. As Sontag writes, “Kiš had a life span that matched, from start to finish, what might have been thought the worst the century had to offer his part of Europe: Nazi conquest and the genocide of the Jews, followed by Soviet takeover.”

About his childhood, the subject of Garden, Ashes, Kiš said, “I lived in fear and trembling. This is my only biography, the only world I know.”

This inheritance hurled Kiš toward literature. He published his first three books before the age of thirty. As he says in Homo Poeticus, “I think of literature as my country of origin.”

He also saw literature as a means for the writer to amend the silences of the past.

“I believe that literature must correct History: History is general, literature concrete; History is manifold, literature individual. History shows no concern for passion, crime, or numbers. What is the meaning of ‘six million dead’ (!) if you don’t see an individual face or body—if you don’t hear an individual story?”

In literature, to paraphrase Sontag, a writer has the privilege to choose his or her lineage. Among his ancestors, Kiš selected Isaac Babel, Jorge Luis Borges and Bruno Schulz. These writers and others helped him to develop the deceptively simple style that courses through books such as Hourglass and A Tomb for Boris Davidovich. About the latter, Brodsky writes, “Some passages could be simply memorized. [I]t achieves aesthetic comprehension where ethics fail. … By having written this book, Danilo Kiš simply suggests that literature is the only available tool for the cognition of phenomena whose size otherwise numbs your senses and eludes human grasp.”

For Kiš, the act of writing entailed a persistent and painful investigation into identity, religion and the weight of the region from which he came. “I write because I call my whole life into question,” he says in Homo Poeticus. He cites literature as “a defense against barbarism” and a way to “give some meaning to the vanity of existence.” Later, he quotes Jean Ricardou: “Without the presence of literature, the death of a child anywhere in the world would be of no more import than the death of a beast in a slaughterhouse.”

As Kiš says on that subject—and as he sought to accomplish in his work, some of which has yet to appear in English:

Literature provides…death with a sense, a significance, a human weight, thereby alleviating and ultimately overcoming it. … What I write isn’t meant to make anyone feel guilty; it’s meant to provide a kind of catharsis. For me the unnamed victim is the greatest victim of History. … To name is to diminish.

KR